David Roelef Doremus was listed as a "surveyor and builder" with an office at 7 Wall Street in 1854. That year he erected a 19-foot-wide, brick-faced house for his family at 741 Greenwich Street, between Perry and West 11th Streets. A short stoop led to the double-doored entrance. Tall French windows graced the second floor, and ornate foliate brackets upheld the cornice.

Doremus had married Ann Van Riper in 1822. By the time they moved into their new home, most of their nine children were grown, although at least two--14-year-old Cornelius David, and 8-year-old Helen Matilda--lived with them.

Doremus was upper-middle class. In 1860 he co-founded the Franklin Savings Bank, Inc., and he was a manager of the North-Western Dispensary on Eighth Avenue. By then he had moved his family far north to 241 West 82nd Street, having sold 741 Greenwich in 1856 for $6,500--around $205,000 today.

Catherine A. Putnam occupied the house in 1862. Calling herself Madame Parselle, she ran a "lying-in asylum," where women stayed during their pregnancies and recovered after birth. Almost all of her clients were unmarried and, in truth, Catherine Putnam was in the baby business.

On June 15, 1862 two advertisements appeared in the New York Herald. One read, "Any person wishing to adopt a beautiful baby from its birth, either male or female, can do so by calling at 741 Greenwich street." The other said, "Children taken for adoption and adopted out at the Infant Nursery; also ladies taken to board by Madame Parselle."

Women who simply dropped off newborns to be adopted rather than board here during their pregnancies were charged $30--around $500 in today's money.

Catherine Putnam styled herself as a doctor, as well. An ad in the New York Herald on June 4, 1864 read: "Madame Parselle--Female Physician and midwife, is now ready to receive all lady invalids; comfortable rooms expressly for ladies during confinement. Call at 741 Greenwich street."

On one hand, her services were invaluable. Unwed women who found themselves pregnant were in serious trouble. The ramifications of being considered a "fallen woman" included public censure and the inability to find work, even as a domestic. At Madame Parselle's lying-in asylum they could essentially hide out until the birth, after which the adoption of the baby was quietly taken care of.

The other side of that coin, however, was dark. In January 1868 a coroner's inquiry delved into the activities of the house following the death of a month-old baby boy. Testimonies of servants painted a grim scene.

Catharine Connolly was a washer woman who worked here two days a week. It was Catharine who had taken the infant's body to the Board of Health for a burial permit. She said in part:

I think I have taken four or five dead children from this house; they were all wrapped up in the same way as deceased was; Mrs. Parselle gave me the children to take; her right name is Putnam...I think there was an average of about one death in two months in Greenwich street; the children generally got placed out.

A clue to the deaths came from Catharine Smith, who helped take care of the newborns. She said, "I give them aerated bread, with milk and sugar, to eat; we boil the bread in water, then put in the milk and sugar." Dr. James W. Ranney testified, "Taking children from their mother's breast and feeding them on spoon victuals tends to shorten their lives." He added, "treating children in this way might be regarded as disreputable."

The verdict of coroner's jury did not fare well for Catharine Putnam. On January 25, 1868 the New York Herald reported, "They find that death was hastened by want of proper care on the part of Catherine A. Putnam, alias Mrs. Parselle, and believe that establishments of the kind kept by her are the means of causing great infantile mortality and tend to the increase of immorality and crime. They recommend that proper steps be taken to break up this and all similar institutions."

The recent history of 741 Greenwich Street may have prompted the wording of an advertisement following Catharine's departure. "Parlors in suites or single; also a Reception Room, with privilege of housekeeping, suitable for genteel parties of respectability; house contains the latest improvements."

The owner, however, seems to have encountered problems finding and keeping a tenant. It was advertised for rent in April 1869 for the equivalent of $2,125 per month today, and again in April 1870, and yet again in March 1873.

That year it was leased by John Smith, who was the victim of a shocking crime five months later. On the night of August 24, 1873, Smith got into a coach and told the hackman, James Byrnes, to take him to a hotel. The next thing he knew it was the following morning. The New York Herald reported, "he woke up in a livery stable yesterday and his money was gone." Smith had had $150 in his pocket--a significant $3,35o today.

Smith had Byrnes arrested. He professed his innocence to Judge Hogan. "Byrnes denied all knowledge of the money and said if the complainant was robbed at all it must have been by some person he took in the coach with him." The judge was not convinced and held Byrnes on the equivalent of more than $22,000 today awaiting trial.

Henry Drugan lived at 741 Greenwich Street in 1889 when he became involved in what devolved into a horrifying incident. On the evening of October 29 Drugan was "staggering along the sidewalk very drunk," according to the New York Herald. He encountered a group of children, including eight-year-old Joseph Brennan, playing in the street. Drugan's obvious inebriation was a source of amusement for the boys.

"The children began to hoot at him and he seized Joe [Brennan]," said the article, "and raising him up over his head he flung him to the sidewalk." Two days later the newspaper entitled an article "Little Joe May Lose His Life," and said, "The child was picked up unconscious and has remained insensible most of the time since." Drugan was arrested for drunkenness and was held in jail "to await the result of injuries inflicted on little Joseph Brennan."

Patrick McGrath, who lived here four years later, was apparently a very sound sleeper. At 4:00 on the morning of January 22, 1893 Policeman McCluskey arrested longshoreman Charles Howard on Bethune Street. The Press said Howard was "weighted down with several suits of clothes." At the station house a letter was found in the pocket of a coat addressed to "Patrick McGrath, No. 741 Greenwich street." Police went to the house to check with McGrath.

"He was asleep, and as Howard had taken away everything, even his hat, he was forced to fall back on the generosity of neighbors to supply him with enough apparel to go to court," said The Press. Howard was charged with burglary and held for trial.

Daniel J. Quinn purchased 741 Greenwich Street around 1897. His wife, Bridget, ran it as a boarding house. Among the boarders that year was Thomas Hogan, who was employed in the New York Biscuit Company's cracker factory on West 15th Street. He worked nights in the cutting room, where the flat rolls of dough were cut into crackers.

On the night of August 28 that year, Hogan and three other employees took a meal break. Upon their return all but Peter Dogget resumed work in the cutting room. He went into the mixing room. Ten minutes later the others heard Dogget scream. The Sun reported he had "fallen or been thrown into a dough mixing vat, where he was cut to pieces by the revolving knives." The coroner's jury ruled his death accidental, but five months later the investigation was renewed.

Dogget's sister received a letter from her mother in Ireland with new information. She said Dogget had been murdered and there was only one witness, an Irish immigrant named Jack. The letter said "the murderer had given him money to get out of the country as soon as possible," according to The Sun. The employees, including Thomas Hogan, were interviewed again. But it seems to have been a mere formality.

"Capt. McClusky said that he knew of no law which would compel the witness of the alleged crime to come back to New York against his will. Therefore, he did not see that he could do anything more about the case at present," said the newspaper.

Also living at 741 Greenwich Street that year was Charles Whitemore, Jr. He seems to have made extra money by working for rookie Policeman Gustave A. Gayer. The New York Herald said on April 20, 1897, "Whitemore is alleged to be a 'stool pigeon' for Gayer." The problem was that the information Whitemore provided was contrived.

The scheme came to light during the trial of Robert McGee, a wagon driver, on April 19. He had been arrested by Gayer for carrying "knockout drops" (the same substance used on John Smith two decades earlier). According to the New York Herald, "McGee alleges that he is the victim of a conspiracy between Gayer, who has been a policeman less than a year, and Whitemore." Gayer's scheme to distinguish himself by making multiple arrests fell apart when the judge in this case realized that Whitemore had been Gayer's witness in at least two earlier cases.

Resident William Reilly was even shadier--and more brazen--than Whitemore. On November 9, 1898 the Morning Telegraph reported, "Daniel McGrady, who lives on the second floor of 3232 West Eighteenth street, was awakened early yesterday morning by feeling a human hand drawn slowly over his face." McGrady realized that a burglar was in his room who, he surmised, might murder him. "He therefore remained perfectly still when the burglar struck a match and held it in front of his face, and pretended not to awake."

The sneak thief was William Reilly who, satisfied that his victim was sound asleep, lit a candle and proceeded to search the room. When his back was turned, McGrady "gave a yell that aroused the household." He rushed to the door where Reilly attempted to block his escape. Although he was knocked to the floor, McGrady managed to get to his feet and run down the stairs and out to the street, shouting for a policeman.

Policeman McDonald accompanied McGrady back to the house. It appeared that Reilly had escaped but, according to the New York Herald, "just as the policeman was about to leave, McGrady heard something stirring under the bed, and Riley [sic] was found hiding there."

Among the Quinns' boarders in the first years of the 20th century was John Lynch. When the United States entered World War I, he joined the army and was sent to fight in France. He would not return home. A private in Company H, 115th Infantry, he was killed in action on September 18, 1918.

The Quinns' son, James, operated a taxicab at the end of the war. On February 8, 1923, he reported his cab stolen and it was spotted at 116th Street and Second Avenue by Patrolman James Walsh. As the officer pursued the cab, he was shot in the stomach. The Brooklyn Standard reported, "The shot is believed to have been fired either by the driver of the taxi or a man inside." Quinn's cab was found abandoned ten minutes later, and Walsh, who was driven to the hospital by a passing physician, survived.

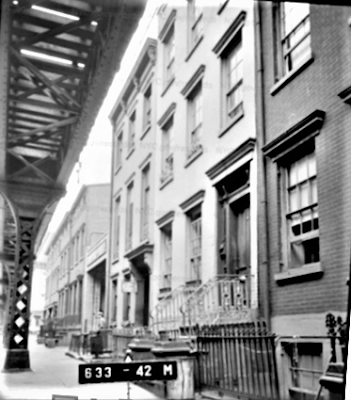

A sign advertising rooms for rent hangs in front of 741 Greenwich Street around 1941. The Ninth Avenue elevated train tracks still ran down the center of Greenwich Street. via the NYC Dept of Records & Information Services.

The house remained a single family home until a renovation completed in 1957 resulted in an apartment in the basement. Although the French windows of the second floor have been replaced, the striking carved Italianate entrance doors survive, as does the overall appearance of David Doremus's 1854 home.

photographs by the author

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

.png)

I have. More information to add to this history of the house

ReplyDelete