Oswald Wirz arrived in America from his native Switzerland in 1880. He opened his architectural office in 1887 and shortly afterward became the in-house architect for the construction and development firm of James G. Wallace. Wallace recognized that the Financial District offered splendid opportunities for speculative office buildings. Interestingly, each of his office buildings in the downtown area was 12 stories tall.

Wirz worked with Wallace through 1895. Among his last designs for the firm would be the Beard Building at 120-122 Liberty Street, running through the block to Cedar Street. His plans, filed in March 1895, projected the cost of construction at $350,000--a staggering $11 million today.

By the time Wirz's plans were completed and before the first shovel of earth had been upturned, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. had purchased the building. (James Wallace, of course, remained as the contractor.) Wirz designed a barbell-shaped structure that provided light and ventilation to the interior offices.

The Beard Building was completed in 1897. Given the overblown elements of many Romanesque Revival office buildings at the time, Wirz's four-part design was relatively understated throughout the lower portions. The Real Estate Record & Guide reported, "The material for the three lower stories is a rich red freestone and for the upper ones pressed brick, in a color to harmonize with the stone." The copper spandrels between the second and third floors had swirling medieval patterns, and each of the intricately carved capitals of the flat piers of this section hid a fearsome face.

Wirz faced the seven-story mid-section in red brick. Six floors of minimal decoration changed at the seventh floor where an elaborate terra cotta frieze ran below the openings and four giant terra cotta ornaments sat below a bracketed intermediate cornice. The eleventh floor openings took the form of an arcade, the carved stone eyebrows all connected. Above another carved cornice the deep-set windows of the top floor gave the impression of a loggia.

On April 24, 1897, the Record & Guide pointed out, "As is well known, the location of the Beard Building is in the centre of the district which is the home of mechanical engineering in this city...Though only just completed two-thirds of the rentable space has already been taken by an excellent class of tenants."

Among those who had leased offices was Henry R. Worthington, Inc., "maker of the celebrated Worthington pumps;" the Pullman Palace Car Co.; the Sims-Dudley Defence Co., "makers of the celebrated dynamite gun;" Standard Elevator & Manufacturing Co., Wheeler Condensing & Engineering Co.; Calvin Tompkins, contractor and dealer in building material; and other manufacturers and dealers in the electrical, mechanical and construction industries.

The light courts between the Liberty Street and Cedar Street sides can be seen in this 1897 photograph. Real Estate Record & Builders' Guide, April 24, 1897 (copyright expired)

On April 14, 1897, The Electrical Engineer, a weekly industrial journal, reported that it had moved its offices into the Beard Building. "It will not only thus be most advantageously situated at the heart of the machinery and electrical district, but will enjoy an increase of several hundred feet floor space."

The American Impulse Wheel Co. was typical of the initial tenants of the Beard Building. The Electrical Engineer, April 14, 1897 (copyright expired)

Not every tenant was involved in the electrical or mechanical trade. On July 14, 1902 The Evening World reported, "Detectives of the Church street station raided an alleged pool-room this afternoon on the fourth floor of the Baird [sic] Building, No. 120 Liberty street." (A "pool room" was an illegal horse betting parlor.) Two men, John Brown and Samuel Marshall, were arrested. "They also secured racing sheets, cashing slips and cards and a 'dope' book,'" said the article.

Undaunted but perhaps a bit wiser, the men continued running the betting office. Three months later, on October 1, Police Officer Charles A. Schultz went back in plain clothes. Leon Stedeker answered the knock and "barred the way." When Schultz identified himself as a policeman, Stedeker replied, "If you've got a warrant, serve it. If you haven't, get the ---- out of here." The Evening World reported, "With that he hustled Schultz toward the stairs and Schultz arrested him."

Stedeker was charged with "interfering with an officer in the discharge of his duties," but he was already under indictment "for running the old Parole Club in Dey street, raided last fall," said the article. The newspaper reported that Stedeker had advised gambling den owners "all over town" to insist on a warrant. The Evening World predicted, "warm developments are expected within two days."

In June 1902 the ground floor was renovated into a restaurant by architect J. C. Westervelt. The remodeling cost around a quarter of a million in today's dollars. The Record & Guide said, "The store and basement are to be remodeled in the fashion of the Child's restaurants throughout the city."

Child's Unique Dairy Co. ran a chain of "Dairy Lunch Rooms" around the city, which, according to Rider's New York City and Vicinity, "have set a standard in the way of sanitary service and excellence of quality at very moderate prices."

That same year the publishers of The Street Railway Journal and the Merwarth Metallic Casket Co. signed leases.

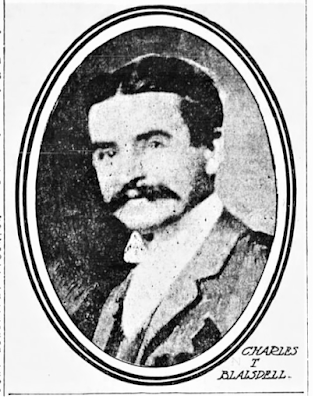

The offices of coal dealers Curtis & Blaisdell were in the building at the time. The firm operated "coal docks" on the East River at East 56th Street. Charles T. Blaisdell worked as the firm's cashier. The young bachelor was fastidious in his appearance and had lived with a roommate, E. E. Reu, in a boarding house on East 57th Street for six years.

On the evening of April 7, 1903 Blaisdell "placed a young woman on a car at Lexington avenue and East Fifty-sixth street" at around 10:30. And then, according to The Evening World two months later on June 25, he disappeared, "as completely as though the ground at Lexington avenue and East Fifty-fourth street had opened, swallowed him, and then closed again."

It was initially thought that Blaisdell had been "lured to the coal docks" and then murdered "for the $1,000 worth of diamonds which he wore and his body thrown into the river." But no body was ever found. Police in various cities, private detectives, and a search by relatives found nothing. Clairvoyants were engaged, but could come up with no leads.

At the rooming house, according to The Evening World, "All of the missing man's clothes, over forty suits, his diamonds, about $4,000 worth, and his personal effects are still preserved...awaiting his reappearance." The firm's manager, James T. Abell, said that a recent coal strike had greatly worried Blaisdell and he had worked late at nights to ensure customers got their coal. "This may have proved too great a strain and when the relaxation came it is possible the shock was too much for him."

The explanation of the dapper Blaisdell's disappearance was never made public. The Evening World, June 25, 1903 (copyright expired)

The roommate agreed, saying Blaisdell "was a man of most excellent habits, neither smoking, drinking, gaming nor in love." He offered, "we are compelled to fall back on the theory that overwork temporarily unhinged his brain, causing a lapse of memory." James Abell added, "The firm and family have spared no expense in following clues."

The mystery ended happily. Late that year the Asbury Park Press reported that Charles T. Blaisdell had been appointed treasurer of the newly-organized Musicians Local Union No. 399 in Long Branch, New Jersey.

A decidedly unusual tenant moved into the building in the spring of 1914, the Ambrosia Milk Corporation. On April 22 that year The Sun reported, "Milk from Normandy in powdered form will be introduced in the New York market with a month by James R. Hatmaker of Paris...Mr. Hatmaker has developed a process for extracting the water from milk without adding or taking away anything from the milk itself."

Hatmaker was confident in his process, telling reporters that "bottled milk will be a rarity within a few years." The Sun wrote, "The Normandy milk will be known as Ambrosia dry milk and will be sold in carefully packed boxes, representing twelve and one-half quarts of liquid milk, by the Ambrosia Milk Corporation of 120 Liberty street." Hatmaker assured America that "in the near future there will be no milk problem any more than there is now a sugar problem or a flour problem."

A much more controversial tenant in the Beard Building at the time was Berghoff Brothers, Inc., "labor adjusters." The term allegedly referred to a security force. The services of Berghoff Brothers, Inc. and similar firms were hired by large corporations--like railroads, coal mining companies, and steel firms--that were dealing with labor strikes. In fact, they were bands of armed thugs sent to crush the strikes with as much force as necessary.

Early 20th century labor strikes were often violent on both sides. Bergdorf Brothers' men were sent to Bayonne, New Jersey during the July 1915 strike against the Standard Oil Company. P. Lee Berghoff was on the scene within the Tidewater Oil Plant with his men. They answered the rioting outside the plant with "sniping tactics," as worded by The Evening World. But it went even further than that.

On July 26 the New-York Tribune reported that Sheriff Kinkead had discovered that houses of workmen "had been under the rifle fire of the guards all night long." The Evening World reported, "a squad of police entered the Tidewater plant and made a demand on P. Lee Berghoff, who supplies the armed guards for the oil companies, to surrender the two men who are said to have fired several shots into the home of John Sudimak...at 3 o'clock yesterday morning."

When Kinkead additionally discovered that the Berghoff men were further "disobeying his orders...by displaying their weapons on the walls of the plant," he arrested 30 guards as well as Berghoff Brothers' superintendent Samuel H. Edwards and P. Lee Berghoff. "All were charged with inciting to riot."

The following year, in August 1916, employees of the New York Railways Company walked out. The New-York Tribune reported on August 6 that although the company "has announced it will employ no professional strikebreakers," P. L. Berghoff said, "that since Friday night that concern has brought in 2,800 strikebreakers from Chicago and other Western cities."

He rather arrogantly went on, "We can throw 10,000 men into New York from Pittsburgh, Chicago and other cities within five days, and in forty-eight hours we can have 5,000 here ready for work." In response, the New York Railways hired a private detective agency that deployed two armed men on each streetcar to protect the motorman and conductor.

On November 15, 1919 the Record & Guide reported that Frederick Brown had purchased the Beard Building. Within only a few weeks he resold it to the Foundation Company, a construction firm with offices in the Woolworth Building. The Foundation Company's intentions to move into 120 Liberty Street were made clear when, on February 18, 1920, the firm purchased four surrounding buildings, "to protect the twelve story Beard building," according to The New York Times.

The storefront was intact when this real estate brochure was published around 1921. from the collection of the Columbia University Libraries.

The firm renamed 120 Liberty Street the Foundation Building. Among the tenants it inherited was the Ambrose Lighterage and Transportation Company, a tugboat concern, run by John N. Sheary. The firm fell victim to what The Evening World described as a "plausible youth" on Saturday, October 1, 1921.

That evening the tugboat Britannia was tied up at Pier B on the Jersey City side of the Hudson River. When the crew went ashore, the cook, Frank Smith, and a fireman, Charles Ericson, stayed back as guards. The Evening World reported that at around 10 p.m. a young man woke them up, handed them $5 and said that Sheary had "ordered them to go to a hotel in Jersey City to sleep, as he had a commission for the tug and was about to put a fresh crew aboard." Obeying perceived orders, the two left the Brittania and check into a hotel. Two days later there was still no sign of the stolen tugboat nor of its "company of conspirators."

Until the third quarter of the 20th century employees were paid in cash. The practice provided thieves ample opportunities to waylay clerks carrying the often substantial payroll. In the fall of 1922 100 workmen of the Foundation Company were erecting a factory building in Long Island City. Fred Shutz, the firm's timekeeper, left 120 Liberty Street on October 21 around 11:00 a.m. with the pay envelopes securely wrapped and tied in a pasteboard box. He took two subways to Long Island City, then started across a vacant lot to the company's construction shack.

He had gone about 200 free when "suddenly a man who was leaning against the fence stepped in front of him and leveled a revolver at him," reported The New York Times.

"Hand over the bundle," he commanded.

Shutz did not react quickly enough and received a blow to the back of the head from another man. The packaged was wrested from him. The newspaper said, "The man in front grabbed him, shoved him against the fence and said: 'Keep your face to the fence or you're a dead man.'" The gunmen got away with $4,700 in cash--around $68,000 today.

In 1978 120 Liberty street (once again called the Beard Building) was converted to apartments, two per floor above the store, and a penthouse level, unseen from street level, was added. The building was frighteningly near the World Trade Center when terrorists flew airplanes into the buildings on September 11, 2001. Unlike so many buildings in the immediately neighborhood, it survived damage.

As New York City struggled to its feet in the next months and years, the idea of a 9/11 Museum and Memorial began taking shape. The September 11th Families Association planned the Tribute Visitors Center and leased the former Liberty Deli space at 120 Liberty Street, appropriately next to Ladder Company 10 and Engine Company 10.

Spokesman Lee Ielpi told The New York Times in September 2004, "Our goal is to create a memorable experience by connecting visitors with the 9/11 community." A few months later, on June 17, 2005, The New York Times reported, "Yesterday, construction began on the Tribune Center, a $3 million visitor center at 120 Liberty Street that will try to provide accurate information about the events of Sept. 11, 2001."

The Tribune Center housed relics, tributes and mementos before the 9/11 Museum. Governor George E. Pataki referred to it as "an interim destination" until the museum could be opened. As it turned out, the 9/11 Tribute Center did not go away after the opening of the 9/11 Museum. On June 21, 2016 The New York Times announced, "Not only is the tribute center still around, it is also to move into a new space nearby, at 88 Greenwich Street, where it will occupy 35,000 square feet."

Today a cafe-bar occupies the heavily-altered ground floor of 120 Liberty Street. The upper floors, however, are nearly untouched since the building opened in 1896.

photographs by the author

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

.png)

This address was also listed as the location of the "Eastern Machine and Tool Co." I assume this was only an office, and the manufacturing was done somewhere else. They built the "Rotadex 5-C Collet Indexer" which apparently could index holes at any angle or degree of a circle, and could also turn spherical parts. I have seen several of these units for sale, but have never seen any paperwork or instruction books for them. Do you have any information on when they might have had offices in the building at 120 Liberty St? I assume this was POST WWII, as the label on the machine I have found gives a 5-digit zip code, which would indicate POST-1964. 5-C Collets were sold starting in the 1930's, and were used for VERY ACCURATE work-holding, in place of the relatively sloppy 3-jaw lathe chucks available up to that time.

ReplyDelete