|

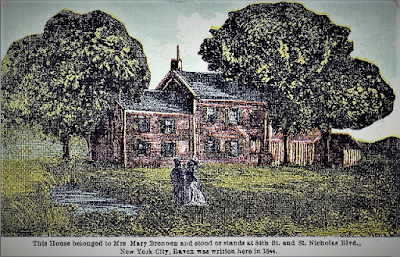

| The farmhouse as it appeared in 1879. The rutty, dirt road is 84th Street. from the collection of the New York Historical Society |

Local lore passed down the story that during the Revolution, Washington and his generals used the house as headquarters. The legend is questionable, since almost every other structure in the area boasted the same claim. But there was one tenant who would draw attention to it later.

Around 1830 the 216-acre farm was acquired by Patrick Brennan and his wife, Mary Elizabeth. Although the Brennans had six children (one historian bumps that number to 10), in June 1843 they agreed to take three boarders--the writer and poet Edgar Allan Poe, his wife, Virginia, and her mother, Maria Clemm as boarders. As a matter of fact, according to Poe biographer Christopher P. Semtner, "Mrs. Brennan later admitted she would have turned him away if he had not pleaded so pathetically on Virginia's behalf."

Virginia had been diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1842. Poe, himself, was suffering from what was then diagnosed as consumption. According to Dr. Appleton Morgan in his 1920 article "Edgar Allen Poe In New York" written for the Manual, "Poe was advised to seek summer quarters among the ancient farmhouses along the Hudson River as no more expensive than the stuffy precincts of Amity Street and Waverley Place, and he found his way to Harsenville and Bloomingdale."

The three spent that summer and the next with the Brennan family. Martha Brennan was about 10 years old at the time, and she later recalled that the Poes had a double room on the second floor of the main house, with "two windows toward the river and two toward the East" looking toward the Bloomingdale Road. Mrs. Clemm spent most of her time there, retiring to a smaller room on the first floor at night.

According to Martha decades later "He was the greatest of husbands and devoted to his invalid wife. Frequently when she was weaker than usual, he carried her tenderly from her room to the dinner table and satisfied her every whim."

|

| from the collection of the Library of Congress |

|

| Poe and Virginia Clemm were first cousins. He was 26 and she just 13 when they married. (original source of the 1847 watercolor of Virginia is unclear) |

There was only one time when Mary Brennan became "vexed" at her boarder. That was when she discovered he had scratched his name into her mantelpiece in his room. General James Rowan O'Beirne, who married Martha, recalled "It was a very quaint and old-fashioned affair with carved fruit and vines and leaves, and Mrs. Brennan always kept it carefully painted. On the day in question Poe was leaning against the mantelpiece apparently in meditation. Without thinking, he traced his name in the black mantel, and when Mrs. Brennan called his attention to what he was doing, he smiled and asked her pardon."

According to Martha, Poe was "a shy, solitary, taciturn sort of man, fond of rambling down in the woods, between the house and the river, and sitting for hours upon a certain stump on the edge of the bank of the river." Her account was backed up by Dr. William Hand Brown who wrote, "It was Poe's custom to wander away from the (Brennan) house in pleasant weather to 'Mount Tom' an immense rock which may still be seen in Riverside Park, where he would sit silently for hours gazing out upon the Hudson." And General O'Beirne added in 1900 "Other days he would roam through the surrounding woods and, returning in the afternoon, sit in the 'big room,' as it used to be called, by a window and work unceasingly with pen and paper, until the evening shadows.

|

| Poe would spend hours sitting the rocky outcrop known as Mount Tom, seen here in 1923. Valentine's Manual of Old New York (copyright expired) |

Poe was very fond of the children and Martha would lie on the floor at his feet while he wrote. "She didn't understand why he turned the written side toward the floor," wrote O'Beirne, "and she would reverse it and arrange the pages according to the number upon them."

Among those writings was "The Raven." It cannot be overlooked that above the door to his and Virginia's room was a small shelf, nailed to the door frame, which held a small plaster cast of Minerva. Behind the bust, according to O'Beirne, was a transom, "a number of little panes of smoky glass." The little piece is almost assuredly the "bust of Pallas" which made such a dramatic appearance in "The Raven."

When he finished the poem, he read it to Mary Brennan and other family members. Then, in January 1845 it was published in the New York Mirror.

Patrick Brennan, in the meantime, was no illiterate farmer. He ran a successful coal business in Bloomingdale and was active in politics, although never ran for office. He was an ardent Roman Catholic and according to The New York Herald, was noted for "aiding in the construction of churches and in the support of charitable and religious institutions."

The wooden house was nearly lost during a violent thunderstorm in the spring of 1854. The New York Herald reported on April 27, "The residence of Mr. Patrick Brennan, situated at the corner of Eighty-fourth street and Bloomingdale road, was struck by lightning, and, miraculous to relate, the fluid but merely stunned Mr. Brennan and family, leaving them stupefied for a short time. Every glass in the building was shattered. It then passed from the house, splitting two large trees; running therefrom to a well, breaking up the platform, and evidently passed down the well into the earth."

Born in 1842, Thomas Brennan was just a toddler when the Poe family rented rooms in the house. Nevertheless he later recalled "watching Poe draw designs in the dust with his cane." The boy first attended Public School No. 9 for seven years, then was sent to St. Theresa College in Montreal. Having graduated at the age of 16, he returned to New York and took a job as night watchman at Bellevue Hospital in 1858.

The wedding of Martha to James Rowan O'Beirne took place in the house on October 26, 1862. The bridegroom would distinguish himself in the Civil War, be active in the pursuit of John Wilkes Booth following the Lincoln assassination, and be brevetted to the rank of brigadier general when he left military duty on January 30, 1866. He was a journalist and author as well.

It appears that Patrick Brennan was incensed at the amount of taxes levied against his property in 1864. A meeting of the Board of Aldermen on November 6 noted he had complained of "illegal assessment" of "his property on the corner of Eighty-fourth-street and Broadway." The minutes of the Board's meeting two months later revealed the Comptroller had been directed to issue a refund to Brennan for $67.91 "being the amount illegally assessed." The refund would amount to just over $1,000 today.

Patrick Brennan died in in the house on December 1870. The New York Herald noted "He was advanced in years and was one of the early settlers of the metropolis" and added "It is worthy of notice that the house in which he resided for forty years is one famous as the headquarters of Washington and in which Edgar A. Poe wrote 'The Raven.'"

The funeral was held in the house on Tuesday, December 6 at 10 a.m. It was followed by a solemn requiem high mass at the Church of the Holy Name of Jesus at the corner of Broadway and 97th Street. Two years later another funeral was held in the house--that of three-year old Mary Eliza O'Beirne, the only daughter of Martha and James.

In the meantime the career of Thomas S. Brennan, who commanded an imposing figure at 6' 4" in height, had soared. In January 1875 he was appointed Commissioner of Charities and Correction, having been responsible for significant reforms in that department, including establishing the Park and Reception Hospitals and the Small-pox Reception Hospital.

|

| Thomas S. Brennan -- Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, April 10, 1875 (copyright expired) |

The Brennan family was soon gone from the old wooden house, however, as development closed in. The rocky landscape that had so enchanted Edgar Allan Poe was being flattened and buildings were appearing on the newly-laid streets.

On July 18, 1888 The New York Times commented "Once an hour, at least, the foundations of the cottage are shaken by the explosion of a charge of dynamite. From the west the miners are almost upon it, and those who are working from the other side will probably reach the centre of the block in a week...The property has recently changed hands, and is now being prepared for building purposes."

With only days left before the Brennan house was demolished, the journalist floridly wrote "But shorn of its fair proportions, a dismantled, shriveled shadow of the cottage in which Poe lived and wrote nearly 50 years ago, the battered and riven walls are still objects of interest to many, and for weeks they have been entered almost daily by companies of relic hunters who are permitted to ply their vocation to their hearts' content by the practical who are at present engaged in blowing up and carrying away the crag upon which the cottage stood."

The extension was currently being used by a blacksmith and contained a forge and "a huge bellows." The article noted that "Much of the lath and plaster has been torn away by relic hunters, but enough remains to satisfy a small army, if wood, plaster, and bricks will satisfy the demand."

One of those relic hunters was William Hemstreet who was interested in the mantel in the former Poe bedroom. Unlike the worthless bits of plaster and lath, contractor Patrick Fogarty charged Hemstreet $5 for the mantel. He supplied a bill of sale dated May 22, 1888 for a "wood mantel of the second story south room of the cottage in 84th street, formerly the resident of Edgar A. Poe; said mantel appearing by its age and construction to be the original one built."

|

| Amusingly, the caption on this late 19th century postcard is unsure if the house was still standing or not. |

A few days later the demolition crew had reached 84th Street and Broadway. The Brennan house, seen only as a curiosity, was reduced to scrap wood and carted off. That it had stood there at all was mostly forgotten within a decade or two.

|

| The site today. photo via streeteasy.com |

And as for the mantel that Poe scratched his name into, upsetting his landlady; William Hemstreet initially installed it in the library his Brooklyn home. Then, in December 1906, he offered it to Columbia University. Despite having (albeit arguable) historic and literary significance, it was placed "temporarily in the Librarian's office, and can be seen on application," according to a 1909 University document.

|

| Columbus University Quarterly, March 1908 (copyright expired) |

.png)

Lost places like this are why 'progress' is bittersweet to me. A boring office building for a piece of literary history. While I understand, the trade off doesn't seem so great.

ReplyDeleteFancy mantelpiece for a house of this type, particularly for an upstairs bedroom. I'd love to see what the rest of the interior looked like.

ReplyDeleteBTW, are tuberculosis and consumption two different illnesses?

That the Brennans lived in that house is odd in itself. One resource spoke of Mrs. Brennan moving "French furniture" into the rooms for Poe and Virginia.

DeleteConsumption was in most cases tuberculosis of the lungs.

My wife, a born and bred New Yorker, is the daughter of John Patrick Brennan. As her family is unrelated to this Brennan family, it’s little wonder that she knows nothing of the lost Brennan homestead.

ReplyDelete