|

| photo by Alice Lum |

George M. Cohan was born on July 3, 1878—one day before the

Fourth of July—with musical theater in his veins. At a very early age he joined his family in

their vaudeville act, “The Four Cohans,” that included his father, mother and

sister.

By his teens, when the talented boy was not wowing audiences

with his singing, dancing and acting, he was composing songs and plays. In 1901 at the age of 23 he produced his

first play in New York, The Governor’s Son.

Undaunted by its luke-warm reception, he followed-up with Running for

Office in 1903. The 20-member cast

included the all four of the Cohans, and George introduced 15 new songs. The manager of the Fourteenth Street Theatre touted

it as “a real novelty.”

|

| One song from The Governor's Son had the shocking title "Never Breathe A World of This To Mother [Father Who's Your Lady Friend?] -- from the collection of the New York Public Library |

Like The Governor’s Son, Running for Office was doomed to

fade into theatrical oblivion.

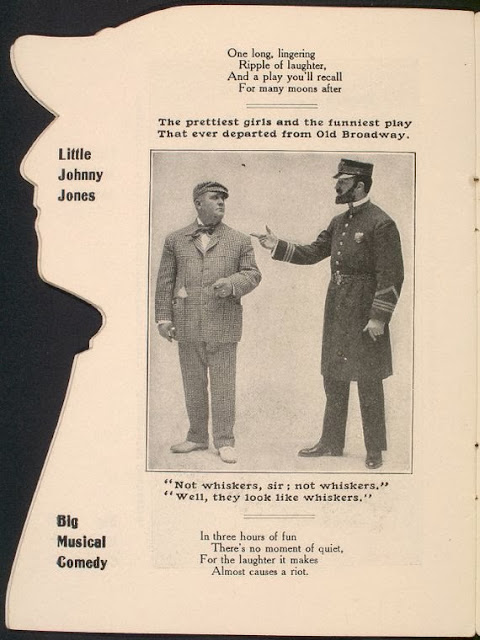

Then the following year George produced Little Johnny Jones. Things were about to change for the 26-year

old George M. Cohan.

As with his earlier projects, along with writing the play Cohan

was his own song-writer and lyricist. Among

the 16 new songs in Little Johnny Jones were two standouts—“Give My

Regards to Broadway,” and “Yankee Doodle Boy.”

The latter foreshadowed the patriotic songs Cohan would pen during

World War I and which would become his hallmark.

Little Johnny Jones was a hit with Broadway audiences as

well as on the road. Each time Cohan

took the play to another city, he was pulled back to New York. On August 1, 1905 The New York Times noted “George

M. Cohan has come back to the New York Theatre with ‘Little Johnny Jones.’ Seven times already has this musical comedy

been in New York, and this is its second visit to the New York Theatre.”

While his hit play was running, Cohan was busy working on a

new musical. In 1905 he simultaneously

produced Forty-five Minutes from Broadway; and on February 11, 1906 The Times

reported “George M. Cohan, who made the unique record of twelve engagements in

New York in his own play, ‘Little Johnny Jones,’ in the eighteen months past,

will return to this city to-morrow evening and present his new musical play ‘George

Washington, Jr.,’ at the Herald Square Theatre."

The newspaper noted that “Like ‘Little Johnny Jones,’ Mr.

Cohan wrote the book, lyrics, and music of ‘George Washington, Jr.,’ staged the

piece himself, and plays the principal role.”

Cohan added to his list of patriotic songs with his new production. “Mr. Cohan sings two new patriotic songs, ‘The

Grand Old Rag,’ [later renamed "You’re a Grand Old Flag”] and a topical song, ‘If

Washington Came to Life.’”

|

| photograph from the collection of the New York Public Library |

By 1920 Cohan had written and produced more than 50

musicals, comedies, revues and dramas.

With the United States' entry into World War I, his patriotic fervor, expressed as music, detonated. In

1917, shortly after hearing that the United States had declared war on Germany,

he wrote “Over There.” The tune became

the virtual rallying song of Americans throughout the war; and was later

resurrected during World War II.

|

| from the collection of the New York Public Library |

In February 1919 Cohan played the leading role in his A

Prince There Was. In its review, The

New-York Tribune wrote less about the play than about its author and

principal actor. “No one is particularly

concerned to find out whether Mr. Cohan is as good an actor as he is an acute

and successful playwright and author. As

a matter of fact he is. Accomplishments

seldom come singly…He keeps in continuous operation a three-ring circus of

which he is the sole performer. Thus in

one ring he is busily pyramiding the plays he is writing, in another he is

juggling chaotic bits of the new musical piece he is producing and in the third

he lightly trapezes into the performance of ‘A Prince There Was.’ These three rings cannot be kept going

simultaneously, of course, but the successions are effected with the smooth

continuity of a protean artist.”

|

| Cohan's 1910 production The Man Who Owns Broadway included this lavish chorus scene -- photograph by Byron & Co. from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York http://collections.mcny.org/C.aspx?VP3=SearchResult_VPage&VBID=24UAYWE24X85&SMLS=1&RW=1366&RH=579 |

One of the three rings of the Cohan circus was about to

disappear.

Later that year the Actors’ Equity Association struck the

Broadway theaters. Cohan opposed the strike which sought

restrictions which would hamper his appearing in his own productions. Although while the strike continued he

donated $100,000 to finance the Actors’ Retirement Fund, many theatrical professionals

never forgave him. He announced his

retirement from acting that year.

The Sun opined on November 30, 1919 “As actor, playwright,

dancer and singer he has enjoyed all the success that might come to any man. And it is as playwright, in such work as ‘Get

Rich Quick Wallingford’ and in ‘Seven Keys to Bald Pate’ that he has shown

ability of a fine order…Mr. Cohan’s present retirement will never be regretted

if it affords him the time to write plays as good as the best of those he has

produced in the past.”

On June 29, 1936 President Franklin D. Roosevelt added to

Cohan’s many distinctions when he presented him with the Congressional Gold

Medal for his patriotic songs that bolstered morale during World War I. The song-writer was the first person in an

artistic profession to receive the honor.

As he aged and his theatrical and musical successes continued,

George M. Cohan was the embodiment of Broadway.

Throughout the decades he represented the profession at the funerals of its greatest names—Barrymore, Belasco and Gershwin among them. In 1941 Broadway feared Cohan’s own funeral

was imminent.

On October 18 he underwent an emergency operation for “an abdominal

condition.” The 63-year old was reported

to be “gravely ill.” That he was

suffering from stomach cancer was not publicized for months. While

he was hospitalized, Warner Bros. was finishing up its musical spectacle based

on Cohan’s life, Yankee Doodle Dandy. Cohan

was played by James Cagney.

The film was released in 1942. George Cohan was by now severely ill and a

private screening was held for him.

Reportedly his comment on Cagney’s portrayal was “My God, what an act to

follow.”

Later that year, at 5:00 a.m. on November 6, “George M.

Cohan, the Yankee Doodle Dandy of the American stage who gave his country its

greatest song of the first World War, died,” as reported by The Times. The newspaper called him “The great song and

dance man—perhaps the greatest in Broadway history.”

The President of the United States sent a telegram to Cohan’s

widow saying “A beloved figure is lost to our national life in the passing of

your devoted husband. He will be mourned

by millions whose lives were brightened and whose burdens were eased by his

genius as a fun maker and as a dispeller of gloom.”

Two days later St. Patrick’s Cathedral was overwhelmed by

the crowds at Cohan’s funeral. “Four

thousand persons including many standees filled the edifice during the high

mass of requiem. Two thousand more,

according to police estimates, gathered outside the cathedral, leaving the

steps clear for the long procession of honorary pallbearers,” said The New York Times.

Among the dignitaries in the church were five Governors, two

Mayors, the Postmaster General, and the former secretary to President Woodrow

Wilson. The honorary pallbearers

included Irving Berlin, Eddie Cantor, Frank Crowninshield, Sol Bloom, Brooks

Atkinson, Rube Goldberg, Walter Huston, George Jessel, Connie Mack, Joseph

McCarthy, Eugene O’Neill, Sigmund Romberg, Lee Shubert, Jerry Vogel and Fred M.

Waring among many others.

Before long a committee was organized to memorialize Cohan on

Broadway. On June 26, 1956 committee

chairman Oscar Hammerstein announced the plans.

The city agreed to improve the block-long triangular Duffy Square and

organizers were already collecting subscriptions towards the $75,000

statue. Hammerstein announced that the

base of the statue would bear the inscription “Give My Regards to Broadway.”

The Times noted that “Irving Berlin, who suggested the

inscription, already has pledged $10,000, Mr. Hammerstein said.”

Georg John Lober was given the commission to sculpt the

statue and architect Otto Langman worked on the granite base. (The pair simultaneously worked on the Hans

Christian Anderson statue in Central Park.)

|

| photo by Alice Lum |

By November 21, 1957 when ground was broken the cost of the

statue and base had risen to $100,000.

On September 11, 1959, following the last Broadway curtain’s drop that evening,

the statue was finally unveiled. “Ten

thousand of the old throng, Broadwayites, entertainers, policemen and

theatre-goers jammed into the area around Broadway and Forty-sixth Street for

the unveiling of a bronze statue eight feet tall at the south end of Duffy

Square,” reported The Times the following day.

.png)

Very neat to see a write up on the history of this statue... one I've seen maybe a thousand times but never really thought about. Nice break from building write ups too! Thank you.

ReplyDeleteI own several pieces of period sheet music and playbills from Cohan productions. The "one liners" used on the covers of the sheet music are hilarious. They were used to entice buyers. The playbills have wonderful advertisements connecting the theme of the stage productions to the product being sold.

ReplyDelete***

Few statues in the city are so well placed and so well deserved..I never pass through Times Square without a tip of the hat to the " The Yankee Doodle Man"..

ReplyDelete