from the collection of the New York Public Library

In 1867 the magnificent Greek Revival structure at the southeast corner of Broadway and Leonard Street was destroyed by fire. It had been built for the New York Society Library in 1838. A few months later, on June 2, 1868, The Sun reported, "Messrs. [Griffith] Thomas & Son, architects, are now engaged, for the New York Life Insurance Company, on what gives promise of being one of the finest and most costly buildings on Broadway." New York Life Insurance Company was founded as Nautilus Mutual Life in 1841, but changed its name in 1845.

In its 27 years in business, the firm had showed remarkable moral growth in its practices. Among the first 1,000 policies issued in 1845, just 15 were upon the lives of women. In his 1906 History of the New-York Life Insurance Company, James Monroe Hudnut said, "it treated women applicants very much as all companies treated sub-standard lives--it did not seek them, and when it accepted them it charged an extra premium."

Other "sub-standard lives" that the firm covered were those of slaves. It originally issued policies to Southern planters on the lives of their slaves--amounting to as much as one-third of the organization's policies. Despite the significant revenue, the board voted to discontinue the practice in 1848.

The firm exhibited further moral advancement during the Civil War. Whether the policy holder was from the North or South, the New York Life Insurance Company stood by its guarantee, paying claims "under a flag of truce," according to chairman Sy Sternberg more than a century later. (That guarantee did not extend to Confederate soldiers, however; but only to private citizens. An article in the Norfolk Journal on February 24, 1871 regarding a law suit filed by a soldier's wife, said the company believed that paying his premium would have been "giving aid and comfort to the Confederate Government.")

As its new building rose, the company was faced with another moral issue. John McRea who lived in Brooklyn, had paid premiums on his $1,500 policy "regularly for many years," according to The New York Times. But then, six weeks before he died early in 1869, "by some oversight or other reason," he failed to pay his last premium. The police was therefore legally void.

On May 27, the newspaper said, "Mr. McRea left a family of four or five persons, and all but one are too small to earn wages for the current necessities of life." The widow explained "her touching and truthful story" to New York Life Insurance Company. After considering all the circumstances and agreeing that legally they did not have to pay, the officials decided "there were good and sufficient moral reasons why the money should be paid."

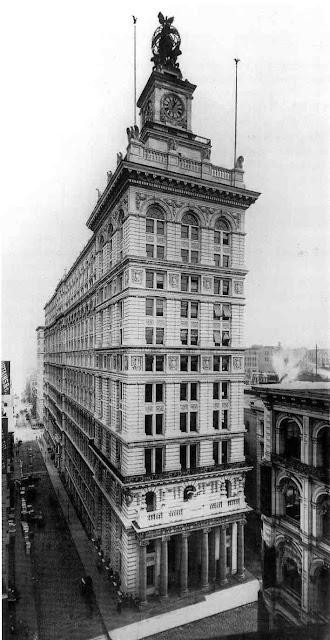

The new building was completed in 1870. Griffith Thomas & Son had designed an impressive Second Empire style structure replete with paired Corinthian pilasters and columns, round-arched openings and a stone balustrade that crowned the bracketed cornice. Carved, spread-winged eagles that perched above paneled pedestals on the balustrade complimented a large sculpture of the New York State emblem.

The front and back sections, which rose four stories above a high basement level, were connected by a long segment one story shorter. The arrangement relieved what would have been a visually ponderous mass.

The shorter, middle section on Leonard Street (left) connected to the rear section, which was as tall as the Broadway portion. from the collection of the New York Public Library

The extensive building held far too much space than the insurance company needed for its own use. A portion of the ground floor was home to the Tenth National Bank for years, and other offices were leased to various firms like textile merchants Whittemore, Peet & Post. On May 14, 1870, the Real Estate Record & Builders' Guide reported, "The Department of Docks has leased the front offices on the second floor of the New-York Life Insurance Co.'s building, Broadway and Leonard st."

The main transaction room, where customers could pay premiums and carry out other business, resembled a banking room. A stenciled ceiling, marble counters and fine carpeting gave a sense of elegance. (print dated 1876, original source unknown)

The Bedford Manufacturing Company occupied a second floor office in 1880. The firm had been organized around 1872 "for the purpose of making a new kind of cloth out of bamboo wood," explained The New York Sun. It was the scene of a horrific incident on November 24, 1880.

Among its employees was English-born Richard J. Scrivner, who became a victim of a general layoff. On November 25, 1880, the newspaper said, "A few months ago the company reorganized, leaving Mr. Scrivner out. Since then his manners and appearance had changed very much."

The day before the article, the 50-year-old had returned to the firm's offices. Despite his no longer working there and the fact that he "seemed nervous and restless," no one asked him to leave. He wrote a letter, then went into a private room and closed the door. The Sun reported, "A few minutes later the clerk heard a pistol shot, and, opening the door, saw Mr. Scriver sitting bolt upright in the middle of a sofa. There was a bullet hole in the right side of his head and a revolver in his right hand." Because the coroner was not able to get to the office until midnight, Scrivers body sat on the sofa "in the same position" for hours.

Julio Merzbacher and Joaguin Sanchez were somewhat autonomously in charge of the Spanish-American business of the New York Life Insurance Company firm. On June 12, 1891, The World explained, "they really carried on a separate partnership business. Their offices were in the New York Life Insurance Building, next to the executives. They had their own force of clerks and kept separate accounts, settling with the Company every sixty days for the premiums and commissions on policies they received." The lack of direct oversight by company accountants provided Merzbacher a sterling opportunity.

In November 1890, Sanchez went to vice-president Henry Tuck to report that he discovered that Merzbacher had been embezzling funds. When the firm moved to prosecute, Sanchez protested, warning that the publicity would cause a scandal. He promised that the missing funds--upwards of half a million dollars--would be repaid within six months. (That amount would translate to more than $16.5 million in 2023.)

Sanchez's trust in his partner was not rewarded. After repaying $60,000 of the stolen money, in January 1891 Merzbacher disappeared. The man who had kept him out of jail was now responsible for the missing funds. On June 27, 1891 President Bears told reporters that Merzbacher "has robbed his partner, Sanchez, of a large sum of money, but Sanchez makes the loss good as far as the company is concerned."

In 1892 New Yorkers celebrated the 400th anniversary of Columbus's discovery of America with a week-long celebration. There were fireworks, a music festival, and the city's first Columbus Day Parade. Major buildings were "illuminated," a tradition from colonial days. On October 10, The Sun said the New York Life Insurance Company's building was "very finely decorated," adding:

...but not half of its beauty can be seen in the day time. Electric lights play the chief part. They are set in rows so closely together than each row looks like a single long light. The globes are of red, white, and blue glass, the colors alternating with the rows. Over the door is a painting representing Columbus, and on either side the figures 1492, formed by red, white and blue incandescent lamps.

Less than 25 years after it moved into the building, the New York Life Insurance Company decided to replace it. On April 22, 1894, the New-York Tribune reported, "The New-York Life Insurance Company filed at the Buildings Department in the last week plans for a twelve-story brick office building." Stephen D. Hatch designed the replacement structure, which survives.

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

No comments:

Post a Comment