When lithographer Major & Knapp published this view of the estate in 1865, the caption erroneously placed it at 73rd Street. from the collection of the New York Public Library

In the 18th century, wealthy New Yorkers escaped the heat and congestion of the city at sumptuous summer estates on the northern half of the island. Most were situated near the rivers to take advantage of the sweeping views and the cooling river breezes.

By 1720, John Bass acquired the tract along the East River from approximately 64th to 66th Streets. In 1747 he constructed a Georgian style residence on the estate "on a pinnacle of rocks overlooking the East River," according to a Bank of the Manhattan Company booklet decades later. Despite its refined details--Chinese Chippendale railings and a handsome half-round attic window, for instance--the one-and-a-half-story wooden structure could as easily have been called a farmhouse as a mansion. Bass and his wife Maria had at least two slaves on the property, Jinn and Henry.

John Bass died in 1768 and was buried on the grounds of the estate next to his wife. The property was inherited by the Basses's daughter, Annetje (better known as Ann) and her husband Johannes, or John, Hardenbrook. Interestingly, Bass's will provided Jinn and Henry with ten pounds each, "in consideration of [their] faithful service, and [they] may choose a master" for themselves, as recorded in the 1899 Abstracts of Wills on File in the Surrogate’s Office, City of New York, Volume VII.

Hardenbrook listed his occupation as carpenter, however the couple's lifestyle suggests he was a well-to-do builder. It appears the couple used the farm as their year-round home.

Directly north of and abutting the Hardenbrook farm was Louvre Farm, a 132-acre estate owned by John and Eleanor Jones. It engulfed the area from today's Third Avenue to the river, and from 66th to 75th Street. The Joneses were among New York's wealthiest families in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Purportedly, following the Revolutionary War the Hardenbrooks leased the estate to General George Clinton--a founding father, future New York State Governor, and future Vice President. Those accounts place him here from 1783 to 1804, during which time, according to The New York Times in 1922, he hosted George Washington who "enjoyed the peaceful river view from beneath one of the ancient trees." Despite the often repeated legend, there is no documentation to support Clinton's residency here.

John Hardenbrook died in 1803. According to the 1810 census, Ann remained on the estate with three white females, none of whom were younger than 45, and two slaves. She died in 1817 and was buried in the family graveyard on the property near her husband and parents.

In December that year Ann's heirs placed an advertisement in the New York Gazette offering the property for sale, describing it as:

...that very pleasant situation, on the E. River, about 5 miles from the city, adjoining the seat of P. Schermerhorn, Junior, Esq., well known as the property of the late Ann Hardenbrook, deceased, containing about 19 acres.

The P. Schermerhorn mentioned in the advertisement was Peter Schermerhorn, the husband of Sarah Jones. The couple had inherited a substantial portion of John Jones's Louvre Farm. They now annexed the Hardenbrook farm to their holdings. In his 1914 Genealogical and Family History of Southern New York and the Hudson River Valley, Cuyler Reynolds explained, "Adjoining [Louvre Farm], on the south, lay Hardenbrook Farm, of about twenty acres, between Sixty-fourth and Sixty-sixth streets, Third Avenue and the East river. This Peter Schermerhorn purchased in 1818, from the heirs of John Hardenbrook, and adding it to his wife's share of the Louvre Farm, gave to the whole the name of Belmont Farm."

Decades later, in 1924, William Rhinelander Stewart, in his Grace Church and Old New York, wrote, "after altering the house for his occupancy [Schermerhorn] removed his residence to it."

The Schermerhorns permitted the extended Hardenbrook family to continue using the cemetery and, in fact, they were obligated to do so. Ann Hardenbrook's will included the stipulation that the owners must preserve "the burying ground forever, with a free passage thereto for the use of my heirs." There would eventually be as many as 14 graves, ranging from the Basses to Mary Adams (Ann Hardenbrook's niece, whose body was interred in 1822).

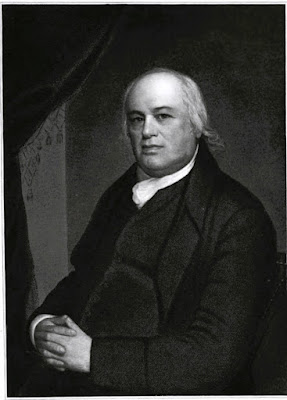

Peter Schermerhorn, Jr. Genealogical and Family History of Southern New York and the Hudson River Valley, 1914 (copyright expired)

Peter and Sarah were married in Trinity Church on April 5, 1804. They had four children when they purchased the Hardenbrook property, and a fifth, James Jones Schermerhorn, was born that year on September 25, 1818. The last to be born was William Colford, who arrived on June 22, 1821.

During the winter season, the Schermerhorn family worshiped at Grace Church. Peter was elected to the vestry in 1820, and was one of the wardens in 1845. But, as The New York Times pointed out generations later, "churches were few and far between above Fifty-ninth Street." The Schermerhorns erected a Greek Revival chapel on Belmont Farm, described by The New York Times as "a unique structure, a low one-story building adorned with a row of columns, giving it the resemblance of a Grecian temple." The newspaper said, "Summer months services were held in the private chapel for the benefit of the wealthy residents, including the Rikers, Rhinelanders, Masons, Joneses, Delafields, Pearsall's, Beekmans, Gracies, Primes, and Astors, who had fine country homes in the vicinity."

On July 9, 1911, years after it had been demolished, The New York Times published an old depiction of the chapel on the Schermerhorn property. (copyright expired)

The 1820 census listed the summer residents of Belmont Farm as Peter and Sarah, four sons under 16 years of age, and six "free colored persons" (four men and two women), at least one of whom was under 16. Although slavery would not be abolished in New York State for another six years, the family's Black servants were all free.

Sarah Schermerhorn died in 1845 at the age of 63. The first census after her death showed Peter, and six children and grandchildren occupying the summer house along with eight servants. (Interestingly, all of the staff were white by now, of French, Canadian and Irish birth.)

Peter Schermerhorn died on June 23, 1852. The sprawling Belmont Farm was inherited by his three sons, John, Edmund, and William, and the widow of his son Peter, Adeline E. Schermerhorn. William Colford Schermerhorn and his wife, the former Ann Elliott Huger Cottonet, occupied the former Hardenbrook house with their five children as their summer home. But after their sumptuous new house at 49 West 23rd Street was completed in 1859, they stopped coming north.

The Schermerhorns' decision to quit Belmont Farm may have had to do with the gradual incursion of development in the area. Between 1833 and 1837 the New York and Harlem Railroad was extended along what would become Park Avenue, and in 1858 horsecars were operating on Second and Third Avenues.

By 1866, the Schermerhorn heirs leased the property to a German immigrant named August Braun, who took advantage of the rapid development of the district. His 50-year lease allowed him to occupy the former Hardenbrook-Schermerhorn house and to operate a "boating and bathing facility" on the land. In addition to this business, he ran the swan boat concession in Central Park. His affluence allowed him and his family to have several live-in servants, according to census records.

In 1877 the Schermerhorn family leased the former chapel building to the Pastime Athletic Club. The club initially paid an annual rent of $180 (about $4,810 in 2023 terms), which included grounds privileges. The members converted the chapel to a gymnasium and clubhouse, while the grounds and Braun's bathing facilities (which they apparently rented from Braun on occasion) were utilized for other sporting events.

In November 1885, staff members of The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record took a leisurely walk along the East River. In the Record's January 1886 issue, one wrote in part:

In an autumn afternoon ramble with our vice-president, as we were walking along the banks of the East River opposite Sixty-sixth Street, we came upon a little cluster of graves. From the tombstones, more or less dilapidated, which marked these 'last homes,' we carefully copied the following inscripti0ns in the private burial-place, which is one of many to be found scattered along the East River shore of Manhattan Island. It is on what is known as the Schermerhorn estate, and when the property was sold some sixty years since to Peter Schermerhorn, the former owners reserved the right of burial.

He went on to record the inscriptions, the earliest, of course, being the plain stones that read merely, "In memory of Maria Bass" and "In memory of John Bass." They extended into the 1820's with extended Hardenbrook family members.

William C. Shermerhorn died on January 1, 1903. The family wasted no time in liquidating the former summer estate only a month later. In recording the sale to John D. Rockefeller, the Real Estate Record & Builders Guide noted, "The property...is the only unimproved plot of its size south of Harlem. The streets, 65th, 66th and 67th, though officially upon the city map, have never been opened." Rockefeller had paid $700,000 for the property (over $22 million today) as the site of his Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research. "The new laboratory grounds...according to present plans, will cover three city blocks," said the journal.

Both August Braun and the Pastime Athletic Club "received their notices to vacate early in 1903," as reported by The New York Times. The New-York Tribune added, "August Braun, who came to this country from near Frankfurt-on-the-Main, has lived in the house since the '60s...He is said to have made many thousand dollars from his boating and bathing business."

The sorely neglected house as it appeared in 1914. Historic Buildings Now Standing In New York Which Were Erected Prior to Eighteen Hundred. (copyright expired)

Six years later the City History Club's Historical Guide to the City of New York mentioned that the "Schermerhorn Farmhouse" was now being used "in connection with the new buildings of the Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research, the erection of which obliterated the Jones [sic] Chapel and the old graveyard where were buried members of the Jones, Hardenbrook and Adams families." (In fact, it appears that the cemetery was simply covered over with fill dirt as the area was elevated and leveled.)

The rear of the house in 1914. from the Frank Cousins Collection of the NYC Public Design Commission.

On October 19, 1914 Greater New York called the Schermerhorn farm house "the second oldest house in Manhattan." The venerable building, having been allowed to deteriorate, was demolished that year.

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

No comments:

Post a Comment