A stoop originally led to the entrance within the larger opening at the left.

In September 1888 architect J. F. Miller filed plans for an ambitious row of homes on the south side of West 115th Street between Eighth and Ninth Avenues (later renamed Frederick Douglass Boulevard and Manhattan Avenue, respectively). Developer P. H. McManus was active in the developing Harlem district, and these eleven three-story and basement houses would nearly fill the blockfront. Each of the high-end residences cost him $10,000 to construct--approximately $295,000 in 2023.

Miller designed the row in groupings of two and three. One mirror-image pair, 314 and 316 West 115th Street, stood out because rather than the red brick and brownstone facades on either side, he clad them in light, cream-colored sandstone. His take on the Venetian Gothic Revival style was understated. Instead of the expected, bold voussoirs of alternating colors almost obligatory in the style, these melted into the facade. Each level of the 16-foot-wide houses was marked by a projecting stone course, and a prominent corbel table upheld the cornice.

No. 316 West 115th Street became home to Matthew M. Looram, the principal in the brokerage firm of M. M. Looram & Co. at 20 Broadway, of which Albert Biddle was his partner.

Matthew Looram's brother and sister, James P. and Catharine, lived with their mother, Mary, at 351 East 39th Street. The three siblings had inherited the house in equal portions upon the death of their father. In 1889 they transferred title to the 39th Street house to their mother.

James P. Looram died there on January 17, 1890. The following year, in July, Mary transferred title to Catherine and moved into 316 West 115th Street with Matthew. Her residency would be short lived. She died on May 21, 1892 at the age of 71. Interestingly, Matthew did not hold her funeral in the parlor, as would have been customary, but at the Church of St. Thomas the Apostle on 118th Street.

Looram drew nationwide attention when he sued the Western Union Telegraph Company. Looram had leased stock tickers from the Gold & Stock Telegraph Company, which he used in his Broadway office. In June 1897, after acquiring the Gold & Stock Telegraph Company, Western Union canceled his contract and removed the machines. An irate Looram demanded the tickers back, protesting that "he would use the tickers only in the business conducted by him and not to run a so called bucket shop." (A bucket shop was an illegal gambling operation that took bets on the rise and fall of stocks.) After a long-fought legal battle, Looram lost his suit in August 1899.

In 1902 Matthew M. Looram erected a 22-room house in New Rochelle, spending over $1 million on the land and building. His former Manhattan residence was now operated as a high-end boarding house run by Mrs. K. L. Reton. Her boarders that year were Frank George White, a member of the American Society of Civil Engineers, and Henry Moore, Jr. Moore was a graduate of the University of Virginia and a member of the New York Southern Society.

Mrs. Reton sub-let the boarding house in 1912. Her advertisement read, "Furnished 10 room house, first class condition, good lease; rent $75; reasonable; going South." The monthly rent was, indeed, reasonable, equal to about $2,000 today.

Eugene Geary moved in around that time. Born in Kilderny, County Cork, Ireland in 1862, he was a journalist, serving sporadically on the editorial staff of different New York newspapers. In 1911 he became editor-in-chief of Beverages, a trade journal.

A proud member of the American Irish Historical Society, Geary was best known for his poetry. His poems were a regular feature of The Evening World and the New-York Tribune. His humorous verse was typified by his "The New Romance," published in The Evening World on May 17, 1913, which poked fun a modern relationships. It began with a couple's marriage ceremony and traced their eroding romance. The ending stanza read:

Now he's gone afar,Future's full of freckles--She? Oh, she's a star--Lots of fame and shekels.Broken was Love's shaft,Once a peacherino,Till the wedded craftLanded out in Reno.

In December 11, 1912 Geary died at the Harlem Hospital at the age of 52. The Evening World said he "was one of the last of the old-time lyricists of the Tom Moore school. His verse had a swing and a music that was irresistible."

In 1917 engineer Cevat Eyüp Tasman, who went by Djevad Eyoub, and his wife Mehlika moved into 316 West 115th Street. Born in Bolu, Turkey on December 26, 1893, he earned his degrees in mining engineering from Columbia University. After graduation he took a job as a mining geologist in New Mexico with the Anaconda Copper Company. It was the beginning of a life-long career in oil exploration. Years later he would help found the Petroleum Administration in Turkey.

The West 115th Street house was offered for sale in 1920 for $18,000, after which Djevad and Mehlika moved to Brooklyn. The Harlem neighborhood at the time was quickly transforming into the center of Manhattan's Black community.

Not all the residents of the former Looram house were upstanding citizens during the Depression years. When William Newman was arrested as a pickpocket on July 19, 1933, The New York Sun reported that his "record includes only nine arrests since 1923."

Carmemn Weeks, the only sister of poet Ricardo Weeks, lived here in the early 1940s. He was a contributor to the Associated Negro Press. In December 1941, Carmemn contracted walking pneumonia. Three months later she was still confined to her bed. Then, on March 7, 1942, The New York Age wrote, "It had been reported that the twenty-four year old girl was improving satisfactorily, until Thursday evening, without permission, she left her bed and went to the bathroom where she collapsed and died of a heart attack."

The mirror-imagine houses retained their stoops in 1941. via the NYC Dept of Records Information Services.

In 1965 315 West 115th Street was converted to apartments, two per floor. The stoop was removed and the entrance lowered to the former basement level.

Then, in 1981, it was purchased by Raven Chanticleer, who began to return it to a private home. Chanticleer was a colorful figure. Born James Watson on September 13, 1928, his parents were sharecroppers in Woodruff, South Carolina. With dreams of becoming an artist and fashion designer, he attended the Fashion Institute of Technology and the Sorbonne in Paris. While in Europe, he took an excursion to London and visited Madam Tussaud's wax museum. He later told a reporter:

I was captivated by this wonderous, vibrant art form. But I was also upset that there weren't any black personalities represented. It was then that I decided that one day I would have my own wax museum. Why? I don't know, just craziness, you know.

Chanticleer returned to New York in 1965 and became one of the first Black clothing designers for Bergdorf Goodman. He founded the Raven Chanticleer Dancers, who performed in nightclubs around Manhattan and wore costumes designed by him.

One of the reasons he purchased the Harlem house was so he could work on his wax museum. But there would be problems. By now the neighborhood was derelict. There was a crack den in the neighboring house and the occupants broke his windows, vandalized his automobile, and set fire to his trash cans. But he persevered.

Eight years later, after spending more than $60,000 on renovations and working on his figures, he opened the Harlem African-American Wax Museum. He told The New York Times, "I created these was figures to keep alive their words and their deeds at a time when too many African-Americans think we have no heroes." Among those heroes memorialized in wax were Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Adam Clayton Powell Jr., Joseph Baker and Fannie Lou Hamer.

And Raven Chanticleer.

During a radio interview in 2001, Chanticleer explained that he included himself "just in case something should happen to me, if they didn't carry out my wishes and my dreams of this wax museum, I would come back and haunt the hell out of them."

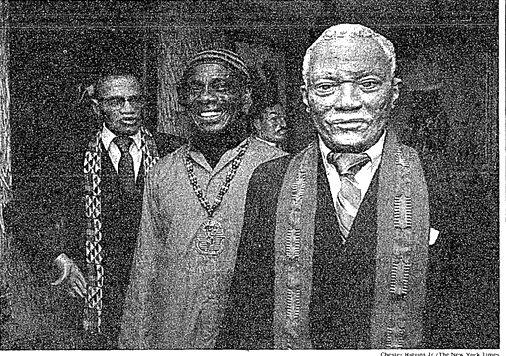

Raven Chanticleer posed between his figures of Malcolm X and Mayor David N. Dinkins in 1993. photo by Chester Higgins, Jr., The New York Times, November 5, 1993.

Something did happen to Raven Chanticleer. He died at the age of 72 on April 7, 2002. A niece told Andy Newman of The New York Times, "We are hopefully, once we get through all the legalities, going to try to see if we can keep it going. That was something he wanted us to do."

But, instead, the figures were reportedly destroyed in 2005. Three years later the house was renovated and today is a single family home above a basement apartment.

photographs by the author

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

No comments:

Post a Comment