photograph by Dayle Vander Sande

In 1892 developer Charles G. Judson completed a row of five upscale rowhouses on the north side of West 102nd Street, between fashionable Riverside Drive and West End Avenue. They were designed by the prolific architect Clarence Fagan True, who typically produced creative takes on historic styles.

For 313 West 102nd Street, True turned to the Flemish Renaissance for inspiration. The three-story-and-basement dwelling was clad in rock-faced limestone, its basement entrance and windows tucked delightfully within an arched recess. The stoop rose beside a full-height bay to a single-doored entrance, decorated with a scallop shell tympanum and foliate carvings.

Elaborately carved Renaissance-inspired spandrel panels between the second and third floors, a blind lancet window sitting atop a half-bowl feature in the peaked gable, and a fearsome gargoyle contributed to True's romantic design.

Willet C. Ely purchased the house on September 16, 1892 for $25,000 (about $768,000 in 2022). If he lived here at all, his was a short residency. He resold the house in October 1893 for exactly the same amount.

The new owner leased 313 West 102nd Street to Elliott Bulloch Roosevelt, a member of one of New York's oldest and most prestigious families. Known as an "Oyster Bay Roosevelt," he was the third of four children of Theodore Roosevelt, Sr. and Martha Stewart Bulloch. His brother, Theodore Jr., was a Civil Service Commissioner who would go on to be President of the United States.

Upon his father's death in 1878, Roosevelt had inherited a personal fortune. He lived the life of a gentleman, going on bison hunting trips to the West, and tiger hunting expeditions in India, for example. Roosevelt maintained a country estate in Abingdon, Virginia where he also had valuable coal mining interests.

Roosevelt was battling demons when he moved in. He had married Anna Rebecca Hall on December 1, 1883. The marriage was strained because of Roosevelt's addiction to alcohol and laudanum (an opium compound intended to relieve pain). The Sun diplomatically said, "Excesses had undermined his health."

photograph by Dayle Vander Sande

On the advice of his physicians, in July 1891 Roosevelt, his pregnant wife, and their children went to Paris. Little Anna Eleanor was 7 years old and Elliott Jr. was 2. There Elliott was placed in the Chateau Sauresnes, described by The Evening Post as "an asylum for the insane." Today we would call it a detox facility.

After nine months in the institution, Elliott Roosevelt sailed home. Anna and the children remained in Paris until the birth of Gracie Hall on June 28. Elliott's treatments had not eased the domestic tensions. When Anna and the children returned to New York they went to the home of her widowed mother, Mary Livingston Hall.

On December 7, 1892, ten months before Roosevelt rented the West 102nd Street house, his 29-year-old wife died of diphtheria. Her death set him into a downward spiral. His increased drinking and drug use worsened when Elliott Jr. contracted scarlet fever and died on May 25, 1893. The Sun said, "the death of his favorite son and namesake, Elliott Roosevelt, Jr., sent him into further excesses."

Living in the 102nd Street house with Roosevelt were his valet and a housekeeper, Mrs. Evans, whom some biographers suggest was his mistress. The Sun said, "he was never estranged from his family, he preferred to live alone." The Evening World, however, was more pointed, saying that here "he has lived virtually cut off from any intercourse with his relatives." He was told pointedly by his mother-in-law that he was not welcomed in her home. And while Elliott kept up a regular correspondence with his daughter, Anna Eleanor (who would go on to marry Franklin Roosevelt and become First Lady), he was barred from visiting the Hall house. His brother Theodore cut all ties with him and urged his sisters to do the same.

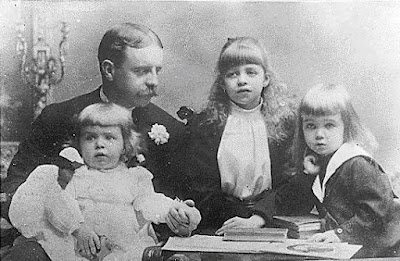

Roosevelt with his children, (L-R) baby Gracie, Anna Eleanor, and Elliot Jr. in 1892. original source unknown

Roosevelt's substance abuse worsened, resulting in frequent hallucinations. On August 9, 1894 he either jumped or attempted to jump from a window at 313 West 102nd Street (there are two versions of the account). In either case, his condition was rapidly deteriorating. Immediately after the incident his valet put him to bed, from which he would never get up.

The Evening World wrote, "Mr. Roosevelt took to his bed Friday. He has been ailing for some years and was not at all in a condition to withstand a severe illness." Roosevelt's doctor, F. W. Holman, was with him for days. The tormented 34-year-old died alone on August 14, 1894.

The following year, on October 16, 1895, 313 West 102nd Street was sold at auction. The listing described, "hardwood trim throughout; newly decorated; gas fixtures; open fireplaces in every room." It was purchased by Dr. Charles Gilman Currier and his wife, Caroline Mary Sterling.

The couple had a two-month-old son, Gilman Sterling when they moved in. Two more children would be born in the house, Dorothy Sterling, who arrived in 1897, and Edith Frederica Sterling, in 1902.

Dr. Currier was well-known for his research on the causes of certain diseases and public health problems. On July 13, 1890, for instance, The Sun had written, "Mothers in the populous tenement districts of this great town may do much toward keeping their babies well this summer if they follow the advice of Dr. Charles G. Currier, published in recent issues of the Medical Record and Medical Journal." Currier discovered that during hot months, "the average milk sold in this city contains many thousands of bacteria in each teaspoonful." He cautioned mothers to boil the milk to kill bacteria.

And the following year he published a pamphlet, "Self Purification of Water," in which he "considers the influence of polluted water in the causation of disease," according to The Sun on March 7, 1891.

The Curriers maintained a household staff of about four. In September 1896 they advertised for a "Young German Protestant, neat and well recommended, as upstairs girl; private house." The term "upstairs girl" in New York City differed starkly from that in the West. In the East, it referred to a more polished servant who could interact with the family and guests. In the West, upstairs girls were the prostitutes who lured cowboys from the second floor windows of saloons.

It appears that working for the Curriers was difficult. The family placed an inordinate number of help-wanted ads for various positions over the years. In December 1909 they had lost three servants. An ad that month read, "American family wants cook, laundress; also upstairs girl; references required."

The Currier family remained at 313 West 102nd Street at least through 1941. Gilman Sterling Currier, now also a physician, married Katharine Nairn Gray on August 30, 1938, eventually settling in Bernardsville, New Jersey. His father died on January 3, 1945 in Greenwich, Connecticut.

The house remained a single family home until 1991, when it was divided into apartments. Other than architecturally unsympathetic replacement windows, Clarence True's fanciful 1895 house is outwardly little changed.

many thanks to Anthony Bellov for suggesting this post.

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

Thanks Tom for another well-researched article.

ReplyDeleteWell done

ReplyDeleteGreat article as usual but your dates in the last paragraph do not make sense. Roland Betts says he bought the house in 1972 and it was already divided into 6 apartments. And you must mean 1892, not 1895, at the end.

ReplyDeleteThe Certificate of Occupancy does not show a renovation to apartments until 1991. The apartments at the time of the Betts purchase were apparently unofficial, a common condition.

Delete