from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York

Deaf-mute children in the early decades of the 19th century had little hope. Considered stupid and inferior by most, their only means of eking a living later in life would most likely be through begging. But hope came with the French Sign Language, developed by Charles-Michel de l'Épée, and in 1814 the first American school for the deaf was founded in Hartford, Connecticut.

In the spring of 1818 the Rev. Abraham O. Stansbury, who came to New York from the Hartford school, was appointed the first teacher of the New York Deaf and Dumb Institute. It opened on May 12, 1818 with four students. Initially funded by donations and what tuition parents could afford, the school grew.

By 1825 the need for a permanent building was evident, but the State Legislature was not easily moved. And so, on March 26, Azariah C. Flagg, the superintendent, loaded students on a train and headed to Albany to prove they were intelligent and being educated. The Register reported, "The scholars of the deaf and dumb institution in New-York...were exhibited in the Assembly chamber, yesterday afternoon, before the members of the legislature, and a large concourse of ladies and gentlemen. The progress of these mutes, in education, is wonderful and highly gratifying."

Legislators asked the children questions, like, "What is the purpose of the Lobby?" These were translated into sign language and answered on a slate. The Albany Daily Advertiser editorialized, "We hope the legislature will be governed by this mute Lobby, if they never were by a noisy one, and give a good round donation."

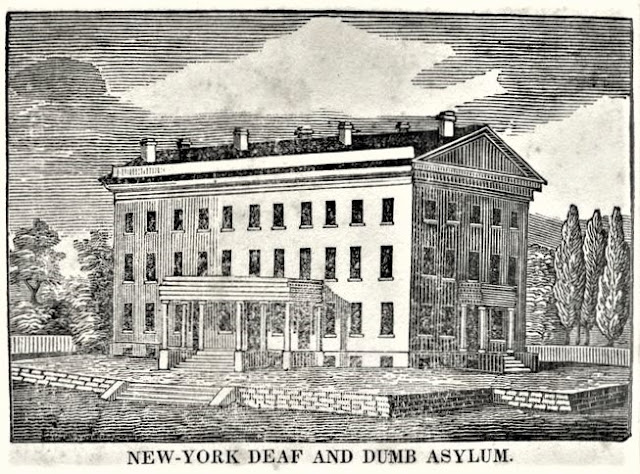

The newspaper got its wish. The cornerstone of the Deaf and Dumb Institution was laid in October 1827. Construction would take two years. The 1857 History of the New York Institution for the Deaf and Dumb said, "the Institution was removed in the spring of 1829, to the new building erected on Fiftieth street, then quite out of town, on an eminence surrounded by open fields and woods." The architect had produced a handsome Federal style building three stories tall above a high basement level. The wide flight of stone steps was protected by a columned portico.

The enrollment upon moving into the new building was just over 50 students. The success of the school was notable and just two years later there were 82 students, 56 of whom "were beneficiaries of the State," according to the 1857 historian.

The students received a similar education to that of public schools--writing, reading, mathematics, history and such--but equally important was the trade department. The mute and hearing-impaired would still face discrimination and misunderstanding after leaving the institution, and knowing how to earn a living was crucial.

As part of their schooling, students were occasionally taken on outings and on what today would be called field trips. In December 1839 they were taken to the Broadway Circus, for instance, and on December 26, 1845 they were taken to see Rembrandt Peale's large moral painting The Court of Death, executed in 1820. Two days earlier, the New-York Daily Tribune had remarked, "those who are there at that hour will witness one of the most interesting scenes it is possible to conceive. Heretofore this painting has made the most marked and lively impression upon the Deaf and Dumb--all the more striking in that they were unable fully to express the intense emotions it excited."

An 1835 print suggests that the original peaked roof was removed and a central tower erected, giving the building a more Georgian look. from the collection of the New York Public Library

As the school grew, the building became inadequate. In September 1847 the directors petitioned the legislature "for a grant of sundry lots of land adjacent to the institution." As always, the request sparked "a warm debate for and against granting the prayer of the petitioners," as worded by the New York Herald. The money was eventually forthcoming and additions were made to the building.

As a condition of the original agreement with the State, four times a year an "exhibition" of the students was held to prove their progress. The remote location of the facility was evidenced on November 19, 1852. In reporting on the exhibition, The New York Times wrote, "A train of cars left the city at 11 o'clock, for the accommodation of visitors, of whom there was a large and most respectable attendance." The children were paraded before the audience to answer questions or otherwise show their education. The article noted, for instance:

A very interesting dialogue (interpreted by the teacher) followed, between Master Barnes, of Utica, and Master Hicks, Long Island, in which the one contended that Bonaparte, and the other that Washington, was the greater and braver man--fully showing considerable knowledge of history.

At the time, despite three enlargements, the building was again being taxed. In 1855, as recalled in the History of the New York Institution for the Deaf and Dumb, "it was in contemplation to enlarge it a fourth time. Meantime, the rapid growth of the great city was threatening to hem in the Institution with a dense population; for whose convenience streets were opened through its grounds; and the space available for fresh air and exercise became very seriously restricted." And so, 37 acres of land in Washington Heights was acquired and construction was started on a new facility.

In 1857 the Institution moved to its new location and leased the old campus to Columbia College, then located on Murray Street at Broadway. The site may well have been chosen by the college's trustees because it already owned a large tract of land adjoining the old Deaf and Dumb Institution.

In 1801 physician David Hosack had opened the first public botanical garden in the United States, the Elgin Botanic Garden. When he could no longer afford to support it, he sold the land to the State of New York. It was given to Columbia College in 1814, after which the gardens were abandoned and they returned to untamed brush.

On April 1, 1857 The New York Times remarked, "There is a lively time now in the College building, preparatory to a change of quarters." The article noted, "By the terms of the late sale of their property, the College may hold possession until the 10th of May, but they are anxious to get away as soon as the alterations now going on in the up-town edifice are completed." The old Columbia building, completed in 1760, was demolished.

The cornerstone of that building, bearing the date 1755, "together with other particulars of the foundation, in Latin, and rudely cut," was salvaged. It was used as the cornerstone of the new Columbia Chapel on the uptown campus, reported the New-York Daily Tribune on August 22, 1857.

The Evening Post, on May 11, 1857, wrote, "The new location of the Collège is a delightful one...The old Asylum Buildings have been altered somewhat, repaired, and greatly improved." Indeed, the New-York Daily Tribune described the updated interiors saying:

The lecture-rooms, library, chapel and residences of the President and the Professors, are very commodious. The lecture-room of Professor McCulloh, the present head of the department of Chemistry and Physics, is particularly attractive, being painted in fresco, having the seats of the students rising circle above circle around the demonstrating table, and furnished with a beautiful dome of glass to admit light.

The Evening Post noted, "A beautiful lawn slopes from the College southward down to 49th Street, and is ornamented by some fine old trees. This will be for the present the main entrance to the College, but as soon as the more extensive grounds northward to 50th Street can be graded, laid out, and properly embellished, the principal entrance will be in that direction."

An extension earlier erected by the Deaf and Dumb Institution is evident in this print. from the collection of the New York Public Library

The chapel was furnished with an organ. Here the President sat on "the library chair of Dr. [Benjamin] Franklin, which contains a brass plate in the back an account of its fortunes since left by the philosopher," wrote the New-York Tribune.

The city's gradual northward expansion was evidenced the following year when the cornerstone of St. Patrick's Cathedral on Fifth Avenue and 50th Street, a block away, was laid.

At the time, the school was pressing to increase the viability of its property for a property campus. Fourth Avenue (later Park Avenue), which now ran through a portion of the old Botanic Gardens plot, "has prevented a determination of the plans for the new edifices," said the New-York Tribune. "If the street can be shut up, a most beautiful and ample design can be carried out."

While that issue was being debated, Columbia College continued to expand. In 1860 a baseball game against New York University initiated intercollegiate sports. The next sport to be included was football, and in 1873, rowing, or crew.

The issue of Fourth Avenue was settled and in 1862 the President's House was erected. One-by-one the campus enlarged, the School of Mines going up in 1872, and enlarged in 1880 and 1884; the Library and Law School was completed by 1884, and Hamilton Hall by 1880. The old Deaf & Dumb Instruction building, slowly engulfed by the modern campus, was relegated to administrative uses.

The days of the venerable building were numbered when this photograph was taken in 1882. photo courtesy John Shekita

By 1892, when the college acquired land in Morningside Heights and began plans to move its campus, the old Deaf and Dumb Institution building had been demolished for nearly a decade.

many thanks to reader John Shekita for prompting this post

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

No comments:

Post a Comment