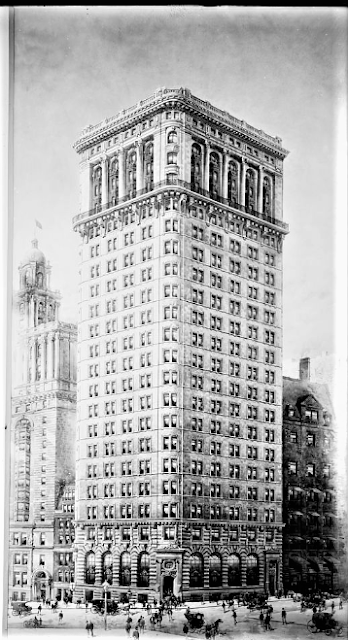

from the collection of the Library of Congress

Established in 1851 as the Hanover Bank, the institution became the Hanover National Bank in 1865. Its success continued until on July 13, 1901 the Real Estate Record & Guide reported that it intended to build a 22-story office building on the southwest corner of Nassau and Pine Streets "from plans by James B. Baker." The Duncan Sherman & Co. building on the site, erected in 1857, would be a casualty of the coming construction.

Completed in June 1903, the soaring structure had cost $1 million to erect--more than 30 times that much by today's terms. Baker's neo-classical office building stood head and shoulders above its neighbors. His tripartite design included a rusticated three-story base, a 15-story midsection, and a four-story upper segment embellished with engaged columns, pedimented metal window framing, and stone balconies. A handsome stone balustrade crowned the elaborate terminal cornice.

James B. Baker's 1901 rendering included foot and carriage traffic on the busy intersection. from the collection of the Library of Congress.

Three months before the building opened the Record & Guide noted, "The Hanover National Bank Building is not filling up as rapidly as some of the others, because the high rental, which is naturally demanded for space in a building so well situated." The rental agents, however, told the reporter they were "fully satisfied with the demand for offices."

And indeed, the upper floors filled with tenants--mostly banking and brokerage firms. Among the early occupants were the large stock exchange brokers Moffat & White, the American Finance & Securities Co., and Spitzer & Co., bankers.

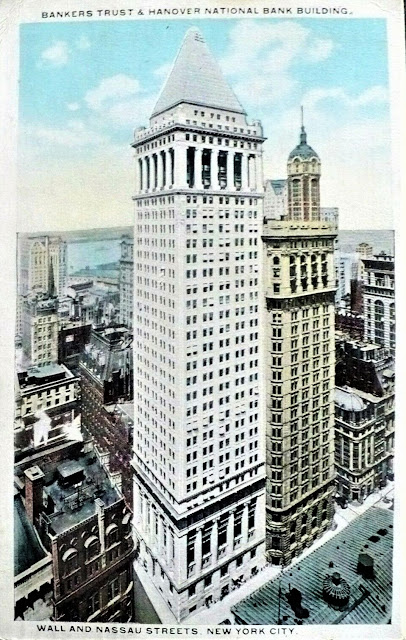

To the left of the Hanover National Bank is the 1897 Gillender Building, and at lower right is the 1842 Federal Hall. from the collection of the Library of Congress.

Two tenants unrelated to the finance industry were the New York and New Jersey Rapid Transit Company, which took space in May 1906; and the offices of the Lunacy Commissioners, which judged the sanity of certain individuals.

The New York and New Jersey Rapid Transit Company was formed to operate commuter railroads between Manhattan and New Jersey. Its general manager, Malcolm R. McAdoo, explained in a letter to The Paterson Morning Call on May 29, 1908, that the large railroads had told him that "the short-haul suburban business was so much less profitable" and that they "would gladly abandon it."

In the 19th century, having a wealthy or cumbersome relative declared insane was a convenient way to get one's hands on their money, or simply to put them out of the way. The problem was such that in 1891 the Lunacy Law Reform League was established to prevent sane victims from being committed to asylums.

A peculiar case came before the Lunacy Commissioners here in November 1906. Valeria F. Sands had been held for 15 years "as a lunatic in the Sanford Hill Asylum at Flushing, Long Island," according to The New York Times on November 17. The newspaper said, "Miss Sands's delusion is that she has a right to the titles of Countess of Balmoral, Duchess of Kent, Duchess of Argyll, Duchess of Orleans, Countess de Rochefouchauld, Barone von Blanc, and Infanta of Spain."

Valeria's father had made a fortune in the East India trade and she had grown up in "one of the greatest mansions ever erected in Hong-kong," according to The New York Times. Valeria's personal fortune was estimated at about $500,000--nearly $15 million today.

An only child, she had been committed by her cousins, Mattie Robinson and Margaret Clayton. Now the two sisters wanted Valeria released for entirely different reasons.

Mattie Robinson declared that her sister wanted Valeria in her own custody to control her fortune, which was being administered by a court-appointed guardian. The New York Times noted, "it has been increasing in value every year." The accusations between the warring sisters erupted during the first session when they "fought with their fists."

After cooling off, the sisters reappeared on November 16. Mattie Robinson told the commission, "She has been kept locked up all these years for no other than mercenary reasons." Now, half of Valeria's fortune, which was held in Scotland, was in jeopardy. Mattie testified that the $250,000 there would revert to the Crown in three years if Valeria did not appear to claim it. "I am going to Scotland next Spring to look after some property of my own there, and Miss Sands wants to go with me and claim her property."

A third session was held on November 23. Mattie Robinson declined to testify this time, telling a reporter, "I would have taken the stand but Mrs. Clayton was present, and I feared she would start a fight. She would hit me with a chair at the slightest provocation."

The case dragged on until December 3 when neither sister got the result she had hoped for. Valeria was deemed, "incapable of taking part in any other amusement than visits to the ladies' parlor" in the asylum, as reported in The New York Times. Dr. Charles L. Dana, saying she was "unlikely to be cured," announced "she was better in the asylum." Dr. Jared G. Baldwin, who had been the Sands' family physician, was given custody of her fortune, with no authority over "the spending of her money beyond approving the accounts submitted by the asylum."

Broker George Wheeler Meacham was another early tenant. He nearly lost his life in the summer of 1907 when he was carried unconscious from the burning Long Beach Hotel on July 29. He recuperated in a private hospital near Central Park. That paled, however, to the threat he encountered in his office two months later.

Meacham was sitting at his desk on September 20 when James Macdonald stormed in, drew a revolver, and accused Meacham of being "attentive" to his wife. The broker insisted he did not even know Macdonald's wife. His earlier near-tragedy turned helpful when Macdonald mentioned dates that Meacham had supposedly carried on the indiscretion with his wife.

The New York Times reported, "To prove that Macdonald was wrong in his suspicions, Meacham brought forth his diary and asked him to compare it with the dates he said Mrs. Macdonald and Meacham had been together." He had been hospitalized throughout the entire period. Later Meacham testified, "He then forced me, at the point of his revolver, to sign a paper to the effect that I did not know his wife, and left, saying that if he ever returned it would be with the intention of blowing my brains out."

But the signed paper did not end the frightening affair. On November 25, a Saturday, Macdonald showed up again. Meacham explained to a judge a few days later, "Then I decided to put a stop to the business, as it was a little out of the usual routine in a New York office to have a man coming in with a loaded gun to interview one at unexpected moments." He had Macdonald arrested at his home on December 3. Macdonald professed that he had returned to Meacham's office merely to apologize for his first visit. He was locked up.

Charles Edwin Ellis was the secretary, treasurer and director of the American Finance and Securities Company until the summer of 1912. After going on a "prospecting trip" through the South, the Far West and Canada, he "became impressed with the insincerity of mankind," wrote The New York Times on August 19. "He would have each man sincere with himself, and sincere with others."

And so, to devote his entire time to the cause of sincerity, he resigned his position with the American Finance and Securities Company and two other concerns. On August 18 he sent a 3,000-word platform for the Society of Sincerists to New York newspapers. Although his plans for attacking the problem were, admittedly, still vague, Ellis could pinpoint the source of the country's problems. "Then let us write across the sky in letters that the whole Nation may read, and spell out as the exact cause of this individual's culpability, the one word--insincerity!" (Ellis's Society of Sincerists was not especially long lived.)

Banking and brokerage firms were often deceived by trusted employees. Such was the case with Kean, Taylor & Co. in 1920. Antonio di Gregario had been hired as a messenger boy five years earlier. By now, the 19-year-old was the head messenger and, as such, was informed ahead of time when deliveries of bonds were expected.

On November 30, 1920, messengers Irving Cohen and Austin Young were on their way to the office of Igoe Brothers with $466,666 worth of Liberty Bonds. They were attacked by three men. Young said later, "One of them pressed a gun to my side and demanded the bag." When he did not release it, he was shot. "I put up a fight and was struck over the head...I tried to hold to the bag, but they got it away from me."

Luckily, Young was not fatally injured. Cohen told investigators, "It looks to me as though some one had tipped them off and they lay in wait for us." It did not take police long to focus on Antonio di Gregario. Pressured, he confessed and identified his brother, Joseph, who had a criminal record, and Antonio Vanilla, as the hold-up men.

Another tenant to fall victim to its own employee was the brokerage firm of Potter & Company. Charles W. Reid was an auditor for the firm. He got himself into serious trouble when he started an extramarital affair in 1923. "Although I am married and have a daughter four years old, I fell in love with another woman," he explained to police two years later.

The other woman wanted more than to be a mistress. She sued for $25,000 in damages for breach of promise. Reid later said, "Fearing that my wife would hear of my misconduct, I did not contest the suit. That was my mistake."

Things only worsened for Reid when friends of the woman threatened to tell his wife and his employer. (Marital infidelity at the time was grounds for dismissal.) In order to pay his blackmailers, Reid began to embezzle funds. "I was trusted by my employers and it was easy for me to pad the payrolls and steal from $500 to $800 a month," he confessed. He had skimmed $4,000 before being caught in 1927--nearly $60,000 in today's money. He insisted "Every cent of this was spend on the young woman or given to the blackmailers." As was so often the case with embezzlers, said The Times-Union, he "blamed his downfall on a woman."

The Hanover National Bank building would fall victim to its taller next door neighbor, the Bankers Trust building.

By now the Hanover National Bank had been renamed the Central Hanover Bank. On September 11, 1929 The New York Times reported that it had sold its Nassau Street building to the Bankers Trust Company. "The purchase gives the Bankers Trust Company control of more than half the block," said the article. Less than two years later, on June 19, 1931, the newspaper reported that the demolition of the 28-year-old Hanover National Bank building had begun "to make room for the new building of the Bankers Trust Company."

many thanks to reader Doug Wheeler for suggesting this post

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

It's a shame a building like that lasted only 28yrs. The replacement building doesn't appear to be significantly taller. Tom, do you know if the two buildings are joined internally?

ReplyDeleteyes, they are joined internally.

DeleteOn October 12th, Shory.com also published a photo and the all-too-brief history of the building on their site, with comments about its rise and replacement.

ReplyDeleteCorrection: shorpy.com

Deleteive an old with 23 WALL STREET address at top left, and small notation with another address of ERNST & ERNST HANOVER BANK BUILDING NEW YORK CITY.

ReplyDelete