from the collection of the Library of Congress

In 1838 the gray granite Halls of Justice and House of Detention was completed. Designed by John Lloyd Stephens, the massive Egyptian Revival prison and courts complex was modeled after a monumental Egyptian tomb. Facing Centre Street, the building engulfed the block back to Elm Street (Lafayette Street today), and from Franklin to Leonard Streets. The ancient, brooding appearance of the structure gave it the nickname, The Tombs.

The New York Times deemed The Tombs "the finest specimen of purely Egyptian architecture to be found in the United States." from the collection of the New York Public Library

On March 7, 1897 The New York Times reported, "Arrangements for the erection of a new City Prison to take the place of the Tombs are fast nearing completion. Plans and specifications have already been drawn, and are merely waiting to be approved before the contracts for the building are given out' and the historic structure so closely associated with New York Criminal annals will soon sink into oblivion."

On one hand the journalist lamented the coming loss of an architectural treasure, but on the other accepted the pragmatism of the decision. The Tombs, said the article, "is inadequate to meet the demands of the criminals of the city. It was built for a prison and not for architectural interest, and in consequence it must be torn down."

Withers & Dickson's design drew from French 16th century architecture, melded with Gothic and Renaissance elements. from the collection of the New York Public Library

Construction on the replacement structure would take five years. The city had approved the Chateauesque style plans of the architectural firm of Withers & Dickson in 1896. But, said the New-York Tribune on July 15, 1900, "when Tammany last came into power it desired to have the spending of the appropriation in its own hands, and so appointed Mr. [Richard] Croker's favorite grandstand builders, Horgan & Slattery, to supersede Withers & Dickson."

The writer explained, "so the consequence is that the building is like a ship with two captains, each with different ideas of what should be done, each giving orders that contradict the other's, the usurping architects pulling down and altering the work of the original architects, and thus prolonging the job and vastly increasing the expense."

Withers & Dickson's plans projected costs at $460,000. The New-York Tribune averred that after Horgan & Slattery became involved, "it was seen that about $500,000 more would be needed, and this was appropriated in 1898." Now, in 1900, "a third appropriation of $350,000 has been demanded."

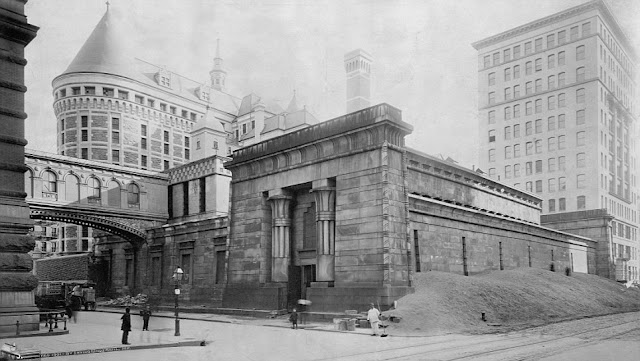

The new City Prison rises on Centre Street while on Elm Street (i.e., Lafayette Street) the remnants of the old Tombs still stand. original source unknown.

In September 1902 architect Frederick Clarke Withers described the nearly-completed structure saying, "The building is a prison, and there has been no attempt to conceal the fact by giving it the appearance of something else. No one who sees it will have any doubt as to the character of the structure. But it is a modern prison, and the men who go to it from the place where they are now confined will appreciate its superiority."

The prison held 320 cells arranged in two four-tier corridors. The New-York Tribune reported on the improved conditions. "The cells are large, and the walls are light in color. The prisoner can walk erect through the massive doorway of a new cell, and need not stoop, as he must now to enter a City Prison cell." Each cell had a cot, a hinged, table, a wash basin and toilet, and a single light bulb. Prisoners were required to take two baths per week either in the shower at the end of the corridors, or in the "plunge bath." Criminals just arriving were often filthy or ridden with fleas or lice. The article said "the newcomers are compelled to undergo the process of scrubbing" in the plunge bath.

The administrative section of the building held counsels' offices, hospital cells, a "search room," and "roomy and well arranged offices." There were also a library on the third floor, a Protestant chapel on the fourth, and a Catholic chapel on the fifth. On the roof was an exercise space. But despite the modern amenities, the new building inherited the old nickname, The Tombs.

Thomas W. Hynes, the Commissioner of Correction, had modern ideas about incarceration, especially concerning young prisoners. He initiated programs aimed at rehabilitation rather than mere imprisonment. On January 28, 1903, soon after the new facility opened, the New-York Tribune reported that he "expected within a week or two to open a school for the boys temporarily confined in the City Prison."

Because the Board of Education could not spare a teacher for the prison, Hynes had requested an appropriation for the hiring of one. He explained that among the 40 young prisoners between the ages of 26 and 21, "Some of them are appallingly ignorant." But, he stressed, "Many of these boys are naturally bright, but they are absolutely unlettered." He felt that a "faithful teacher" would be able to "drive the rudiments of learning into some of their minds during their temporary detention."

By the end of the year David Willard had the title of "principal of the school in the Tombs." A journalist who visited the schoolroom "where the prisoners sat on wooden benches" in December that year wrote:

One would hardly realize that every member of the class was charged with crime. The majority looked more dirty than wicked. Many seemed to have just tumbled out of bed and had not bothered even to wash their faces nor brush their hair. And yet on either side of one frowsy looking lad sat two prisoners who had been bank clerks. Their clothes fitted well. their linen was clean, and one wore a stickpin, which the frowsy headed lad squinted at with a grin.

The boys had good reason to behave and learn. David Willard's assessment of the prisoners--good or bad--was taken into account when the possibility of their release neared.

Prisoners were taken from The Tombs to the Criminal Courts Building (right) across Franklin Street on the elevated "The Bridge of Sighs."

Less than a decade after the model prison had opened, there were troubles. On November 17, 1911 The Evening World began an article saying, "Some relief is promised from the scandalous overcrowding of the Tombs." The current Commissioner of Corrections, Patrick H. Whitney, assured "I'm doing my best to remedy the overcrowding," while admitting, "There are two prisoners in each cell in the Tombs...but every prisoner should be alone as the law requires."

Two years later nothing had been done. In 1913 a well-spoken prisoner, Julian Hawthorne, wrote a detailed description of his time here. He said in part:

It is a unique place, a devil's ante-chamber, where almost anything except what is decent and orderly may happen. It is not so much a prison or penitentiary as a human pound, where every variety of waif and stray turns up and sojourns for a while; murderers, pickpockets, political scapegoats, confidence men, old professionals, first time offenders, even suspects afterward to be proved innocent.

Despite the challenges, the Department of Corrections continued to focus on rehabilitating youthful offenders. On February 26, 1928 The New York Times reported on the work of the Committee on Boys in the City Prison of the Public Education Association. It said that of the 2,290 boys incarcerated in The Tombs in 1927, 916 had been "advised and aided" by the group. "Many of these boys, who had reached only the border land of crime, are now leading useful lives," said the article. The Committee on Boys investigated the prisoners' background and focused on "cases where abnormal home conditions or unemployment, rather than inherent viciousness, seem to be responsible for the boy's plight."

In the meantime, proposals to correct the overcrowding continued. In 1930 the State Commission of Corrections "condemned the practice of confining more than one prisoner in a cell in the Tombs and declared that New York City should lose no time in correcting conditions there," according to The New York Times on February 22. There were 419 cells and 669 prisoners at the time. The Commission urged the construction of a supplementary uptown jail.

Still nothing had happened four years later when, on June 17, 1934, The New York Times reported, "If Mayor LaGuardia has his way, the gray, dingy Tombs, or City Prison, and its dull-red neighbor, the Criminal Courts Building, will be torn down to make room for a skyscraper combining the functions of both." The article mentioned, "The Tombs prison...is connected with the Criminal Courts Building by the Bridge of Sighs over Franklin Street."

While the debate went on, the fact that the prisoners in the overcrowded facility were, in fact, not mere statistics but human beings was illustrated by a heart-rending incident on August 7, 1934. A patrol wagon containing five prisoners pulled up to the Lafayette Street entrance that afternoon. The driver had been, most likely, unaware that a dog had been trotting alongside the vehicle. The New York Times reported, "The prisoners filed into the entrance, under the watchful supervision of two policemen." The dog, described by the newspaper as "mostly black, two-thirds chow, one third spaniel," scurried up, looking for his owner.

"The dog tried to follow the last prisoner, but the policemen, who could think of no reason why such a bright-eyed, scrappy little dog should be jailed, interfered." Locked out of the jail, the dog refused to budge, instead it sat by the doors and continuing "its mournful plaint."

An attorney took charge of the dog, taking her to the New York Women's League for Animals. The group agreed to hold her until her owner's release. "Pending the claim, the league said, the dog would be called Nancy, after the lady in 'Oliver Twist,'" said The New York Times.

Finally, after more than 25 years of debate, in January 1937 Mayor Fiorello La Guardia sent a bill to Albany requesting $15 million to erect and equip a replacement for the City Prison and the Criminal Courts Building. Construction of the massive Criminal Courts Building and Men's House of Detention, designed by Wiley Corbett and Charles B. Meyers, at 100 Centre Street, directly across the street from The Tombs, began in 1938.

The new Criminal Courts complex looms behind the still standing old Criminal Courts Building (left) and The Tombs in 1941. The New York Times, June 29, 1941

Today an urban oasis, the Collect Pond Park, occupies the site of The Tombs.

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

Julian Hawthorne was indeed well spoken - he was the son of author Nathaniel Hawthorne. Himself a reasonably successful journalist and writer he served a year in prison (in NYC and Atlanta GA) for mail fraud-participating in a scheme to sell three and a half million shares in non-existent silver mines.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Tom, for this great article about the history of the Tombs and for the article you wrote in 2011 on the same subject.

ReplyDelete