from the collection of the New-York Historical Society

On June 13, 1867 The Brooklyn Union anticipated that the theater portion of the nearly-completed Banvard's Museum would be a failure. "In the first place, the stage is altogether too small for any respectable scenic show, and the orchestra is perched up in the proscenium arch, facing the audience. This is an obsolete French idea." The article said, "If Mr. Banvard had a little more experience in the theatrical business he would know better than to waste his money in so foolish an experiment."

Banvard's double-purpose structure--a museum on the lower levels and a theater on the main floors--was a rather inelegant take on the recent French Second Empire style. Shops occupied the ground floor on either side of the centered entrance doors. Three stories of red brick supported a double-height mansard fronted by a cast iron balcony.

Banvard's double-purpose structure--a museum on the lower levels and a theater on the main floors--was a rather inelegant take on the recent French Second Empire style. Shops occupied the ground floor on either side of the centered entrance doors. Three stories of red brick supported a double-height mansard fronted by a cast iron balcony.

The museum section featured the expected curiosities like stuffed animals and exotic attractions of questionable origin. Yet Banvard offered a feature that might today be considered a house of horrors. The Buffalo Sunday Morning News described "a representation of an extremely orthodox and old-fashioned hell, with as many of the traditional horrors of eternal punishment as could be depicted in the space at command." The article described "real flames" which erupted here and there as actors dressed as demons "made sport of as many tormented beings," and "nondescript animals crawled in and out of darksome grottoes, and pandemonic music mingled with human groans and yells."

Banvard's Museum opened in July 1867 with a variety show that did not especially please the critic of The New York Times. He ended his column saying the acts were "not strictly entertaining." Only a month, despite a hit play, a review in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle hinted that Banvard's Museum was closing under his ownership. It said that Nobody's Daughter "has been so decided a success...that it seems a pity to withdraw it from the boards. In fact, if the Museum were not about to pass into the hands of other parties...we have no doubt Nobody's Daughter would run to a paying business down to the holidays."

Banvard's failure was due not only to the lackluster theatrical performances, but disappointment in the museum. The New York Times reported on March 18, 1868, "When Banvard's Museum was started a year or two ago, we were led to expect that it would become a repository for scientific collections and natural wonders, and a place which, while furnishing delight to our country cousins and our city juveniles, would also offer means for study, thought and observation...Those who entertained such ideas soon discovered that they were doomed to disappointment."

George Wood had taken over the establishment, which was closed "in order that it may be enlarged, restocked, and furnished with novelties for the entertainment of the curious," reported The New York Times. Wood's Museum and Theatre opened for the 1868 fall season. A 30-cent ticket admitted the buyer to "ALL the attractions," according to an advertisement on December 16, 1869. Another ad on the same page note "all for One Admission, including the Wonderful Stone Giant."

That attraction was touted to be The Cardiff Giant--the 10-foot tall petrified body reputedly discovered on a farm in Cardiff, New York. Almost immediately a letter to the editor signed by four gentlemen appeared in The New York Times. It said in part, "We desire to inform the public through your columns that the statue now on exhibition at Wood's Museum is a plaster cast taken from the original by C. F. Otto, an artist of Syracuse, without our knowledge and consent." The real giant, it said, was on display in the State Geological Hall in Albany.

George Wood's venture lasted a decade. When veteran theater operator Augustin Daly took it over in 1879, he initiated a complete make-over. The museum portion was eliminated ("except the Cardiff Giant," said The New York Times on September 16, 1879, "which, being an exceptionally ponderous wonder, still lies quietly inurned in some place in the building"), and the building renovated. The New York Times said, "Mr. Augustin Daly having taken the old pile in hand, has wrought in it a wondrous transformation."

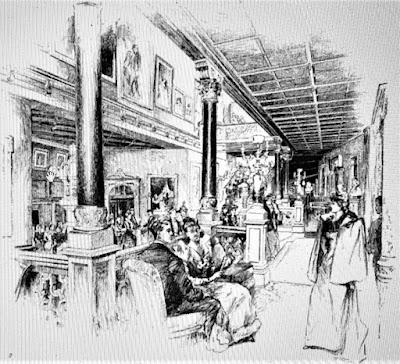

Among the exterior changes was the addition of a two-story portico, "the pillars of which are a curious but very effective combination of the Egyptian and fluted Doric styles of art." The interior renovations cost, according to The New York Times, $20,000--or about $529,000 today. "It is the picture of a parlor in a gentleman's mansion," said the newspaper. "There are mantlepieces, magnificent mirrors, a piano, rich tapestry, soft Persian carpets, to tread upon which is luxury, and a wall-paper of a most beautiful pattern." The auditorium had been enlarged, now seating 1,400 persons. "The general style of the house is a modification of the Elizabeth, the style of Queen Anne's time prevailing in the private boxes, which are unusually spacious and well appointed," said the article.

Augustin Daly presented his own plays starring some of the best known and popular thespians of the day. On October 1, 1879 The New York Times said his "well-known play, 'Divorce,' was revived last evening under pleasant circumstances, and was received with a good deal of favor...The drama is full of excellent theatrical material." Clara Morris starred and the critic raved that her "genius...lit up the scenes of the drama."

President James A Garfield was shot on July 2, 1881 and died on September 19. The entertainment industry nationwide shut down out of respect. After his body lay in state in the Capitol Rotunda, the President's funeral was held in Cleveland on September 26. Daly's decision to open his theater that night caused some serious indignation.

Daly added the portico with its lacy cast iron railing overhead. from the collection of the New-York Historical Society

The New York Times reported that a man named Edward T. McDonald, "took his stand in front of the building, and by his vehement language and gesticulations soon caused a crowd of several hundred people to gather about him." Cries of "Down with the theater!" "Burn the building!" erupted. Barrels were rolled to the theater, one of them filled with tar, and McDonald attempted to set them on fire. Luckily, police responded before any damage could occur. "None of the people inside of the theatre were aware of the disturbance until it was all over," said the article.

Daly refurbished the theater again during the summer of 1885. A new marble-tiled lobby floor was installed, new chandeliers brought in, new seating, and the entire interior redecorated. In the auditorium, said The New York Times on September 6, "the same mahogany dado noticed in the rotunda has been carried around the whole interior of the house." The redecorating cost Daly a quarter of a million in today's dollars.

Star actress Ada Rehan was appearing in The Taming of the Shrew in March 1889. On March 20 a notable figure occupied a box during the matinee--Florence Cleveland whose husband's administration as President of the United States had ended only two weeks earlier. In the decades before Secret Service men would have surrounded a former First Lady, she entered the theater with her friends like the other patrons.

The New York Times reported, "Mrs. Cleveland was among the leaders of the applause which was liberally showered on this excellent actress. The wife of the ex-President apparently thoroughly enjoyed the magnificent performance given by Mr. Daly's company, and after the curtain had fallen she and her party lingered for some time in the foyer examining the collection of rare pictures."

Augustin Daly died unexpectedly on June 7, 1899. Even before his funeral the fate of his theater was being discussed. On June 9 The New York Times reported, "Mingled with the general sentiment of regret at Mr. Daily's sudden demise there was much anxiety and concern regarding the future of the theatre established by him. Persons who for many years have regarded Daly's Theatre as one of the worthy institutions of New York were eager to learn whether there was any provision for its permanent continuant."

On July 23, 1899 The New York Times reported that the theatre was not sold yet, but offers to negotiate were flowing in. Florenz Ziegfeld cabled the Daly estate's attorneys saying "Please inform executors I desire to negotiate." Another article said, "Managers from all over the country and from abroad have been telegraphing and cabling their intentions to negotiate for the property."

The process proceeded with lightning speed. On July 25 The New York Times reported, "Daly's Theatre passed yesterday into the hands of Charles Frohman." The impresario paid "about $100,000" according to the article, over $3 million in today's money. As part of the deal Ada Rehan "secures all the scenery, properties, and wardrobe of the Shakespearean repertoire and comedies of her selection."

Charles and Daniel Frohman retained the profitable Daly's Theatre name. It opened under their management in September 1899 with The King's Musketeer starring the popular actor Edward Hugh Sothern.

An elaborate stage set for The Cingalee in 1904. photo by Byron Company from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York

Four years earlier Oscar Hammerstein had erected his massive Olympia Theatre on Longacre Square. It had signaled the first step in the migration of the theater district to what would be renamed Times Square. Daly's Theatre would hold on for several years even as newer, more elaborate venues opened ten blocks to the north.

A surprising actor appeared in George Bernard Shaw's Cashel Byron's Profession on January 8, 1906--prize fighter James J. Corbett. Perhaps surprisingly, The New York Times theater critic was not totally negative, saying in part, "For a few moments--notably during the first act--there seemed to be some method in this madness." Nevertheless, he concluded Corbett would be best advised to continue boxing.

The following year the Schuberts took over the theater, only to almost immediately pass its management to Henry Miller and Margaret Anglin before the 1907 season opened. Once again the name remained Daly's Theatre. The pair managed to provide legitimate theater until 1914, when Charles A. Taylor took over the lease. The end of Shakespeare and Shaw was evident when, on January 12, 1915, The New York Times ran the headline "Alas, Poor Daly's! Burlesque Reigns." The article began:

Shades of Augustin Daly; shades of Ada Rehan's Katharine; shades of all the traditions of the spot where John Drew played when he was young and where Mrs. Gilbert played when she was old! In streaming red letters a huge sign yesterday announced to Broadway, Daly's Theatre, The Home of Burlesque.

In the lobby, where once had hung photographs of famous actors in historic roles were now "garish pictures of 'queens' in fleshlings."

Daly's Theatre (right) sat along a much-changed block in 1910. from the collection of the New York Public Library

It may have been that article which prompted a raid on Daly's Theatre less than a month later, on March 3. More than 1,000 men paid to see The Merry Maids followed by "a chorus girls' contest." They would see only a portion of the first attraction.

Later that year the venerable theater was converted to a silent movie venue. It opened on December 12 with a screening of Virtue (which had been banned by Philadelphia censors). The theater lasted only five more years. On July 3, 1920 The New York Times reported that the "famous home of the drama will soon be torn down for [an] eight-story structure."

That building, designed by Louis Allen Abramson, was recently demolished to make way for a glass and steel tower.

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

Frances Folsom was the wife of President Stephen Cleveland, whom she married in 1886 when she was 21. She was his ward. She was related to Commorodre's Oliver Hazard Perry and Matthew Calbraith Perry.

ReplyDelete