|

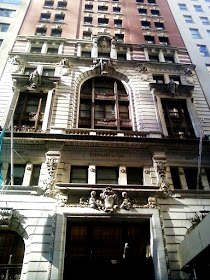

| The innovative six-story bay draws the viewer's eye upward -- photo by Alice Lum |

The first decade of the 20th century was exciting

both from architectural and engineering standpoints. Steel skeletons made higher buildings

possible and passenger elevators made them feasible. Suddenly Manhattan’s financial district was

falling under the shadows of skyscrapers.

Yet not everyone was pleased with the soaring new

structures. Fear of fire in upper floors

and structural stability were on the minds of many. In May 1902, A. J. Bloor wrote in The

Architects and Builders’ Magazine, “It is to be feared…that calamity is also in

store for the public as regards cases of inadequate protection of their steel

skeletons from contact with the air, and from consequent rust, corrosion and

constructional dismemberment.” The same

retired architect added in a letter to the editor of the New-York Tribune a year

later, “firemen are ‘afraid’ of the skyscraper. They have good reason to be.”

But the skyscraper was here to stay and the Trust Company

of America was about to add one more. On

May 20, 1906, the New-York Tribune reported that the financial institution was

demolishing the 25-year-old United States Bank Building at 41 and 43 Wall

Street as well as its next door neighbor, the Metropolitan Trust Company at 37-39 Wall Street. The newspaper was amazed that the soaring

10-story building was already being razed for a yet taller structure.

“On the site of the two buildings the Trust Company of

America is to erect a twenty-five story skyscraper,” it reported. The cost of demolition alone would run

$12,000.

|

| The New-York Tribune published a sketch of the anticipated building in 1906 (copyright expired) |

Four months later, architect Francis H. Kimball completed his

plans which promised “a new skyscraper, which will surpass in many respects anything

yet seen in this city,” said The Tribune.

The Trust Company of America would take the first floor and basement, the main floor being the banking department. “The banking rooms on the first floor are expected to be the most

magnificent and elaborate offices in the city,” said the New-York Tribune.

The banking room would rise two stories with soaring pillars supporting the ceiling. The

teller cages were fashioned of marble and bronze, and the woodwork was

mahogany. “The outside of the building

will be constructed of marble for seven stories,” said the newspaper, “the

remaining eighteen being of red brick with marble trimmings.”

|

| photo by Alice Lum |

The white marble base exploded in ornate Beaux Arts

decoration. Above the central opening,

two cherubs held a garland that draped down both sides of the window

frame. Carved lions heads, scrolled

brackets, fruits and flowers dripped from the façade. Above, the red brick central shaft, which

showed more restrain, was interrupted by an interesting six-story bay. The uppermost floors returned to white marble

sheltered by an overhanging cornice.

|

| photo by Alice Lum |

Kimball and the Trust Company of America added one

especially novel concept. The Mills

Building, a 10-story structure at 15 Broad Street, was L-shaped, with a

portion of the building at 35 Wall Street. Its offices were cramped and outdated.

As the new skyscraper rose, entrances were opened at each floor

that connected the two buildings, allowing the tenants of the Mills Building larger

spaces.

On December 16, 1906, six months into construction, an

explosion below street level rocked the site.

“With a crash which could be heard for blocks and which was followed by

the blowing off of steam, more than seventy-five feet of asphalt covered street

in Wall street between Nassau and William streets, sank from three to eleven

feet yesterday afternoon,” reported the New-York Tribune.

A 16-inch steam pipe owned by the New York Steam Heating

Company had broken, releasing a geyser of steam and opening a gash in the

street 75 feet in length in front of the Trust Company Building and 40 feet by

20 feet near William Street.

Businessmen fled, fearing that the Trust Company Building would come

crashing down. Edward S. Jarrett,

treasurer of the Foundation Company reassured the public saying, “The foundation

of the Trust Company building is damaged in no way, and I do not believe that

any other buildings are injured.”

The building was completed in 1907 and, along with the Trust

Company of America, financial concerns like Eyter & Co., dealers in

high-grade bonds; and Shoemaker, Bates & Co., publishers of the Weekly

Market Review moved in. The year would

be momentous for the Trust Company of America for another reason.

In October of that year, a failed attempt by brothers Otto,

Augustus and Charles Morse to corner the market in United Copper Company sent

Otto Morse’s brokerage house, Gross & Kleeberg, into bankruptcy. When United Copper collapsed, the State

Savings Bank of Butte Montana became insolvent.

Because the Montana institution was a correspondent bank for the

Mercantile National Bank in New York City, depositors panicked and mobbed the

bank. Runs on other banks ensued.

Within the week, crowds were swarming the Knickerbocker Trust

Company. The New York Times wrote, “as

fast as a depositor went out of the place ten people and more came asking for

their money.” After three hours and $8

million in withdrawals, the Knickerbocker shut its doors. And now the panic spread to the Trust Company

of America.

With nine banks in failure, there was a run on the Trust

Company of America. The bank survived the first day of withdrawals, but could not last another business

day. The Trust Company of America sought

the help of J. P. Morgan who met with other bankers and the Secretary of the

Treasury, George B. Cortelyou. After an

overnight audit of the Trust Company’s books, Morgan announced “This is the

place to stop the trouble, then.”

The government supplied an influx of cash in the form of

$8.25 million in loans to allow the Trust Company of America to stay open the

next day. It was the first step in the

process that, within a few days, staved off a financial collapse.

Along with financial firms, legal offices filled the

building. In 1908 Murray, Prentice &

Howland, specialists in banking law, moved in and would stay for decades. By 1914 Blandy, Mooney & Shipman,

attorneys, was here.

In 1918, Equitable Trust Company took over the banking rooms

of the Trust Company of America. By now, attorneys Murray, Prentice & Howland had become Murray, Prentice &

Aldrich. Perhaps their most visible and

wealthiest client was John D. Rockefeller. In 1921, the attorneys were in Federal District Court fighting a governmental suit against the millionaire for $292,678.78 in unpaid income tax going

back to 1915.

Four months before the onslaught of the Great Depression,

the Interstate Trust Company opened its headquarters here. It was one more in a string of banking firms

that would use the cavernous first floor as their headquarters. In October 1941, the Public National Bank and

Trust Company opened here, and in 1959 the Bank of Nova Scotia Trust Company of

New York began operations.

In the meantime, in 1954 the New York Institute of Finance

moved in. The unique school provided education

in securities markets. “At the start in

1921 it was solely for Exchange employees,” explained The New York Times on September

12, 1954. “In 1930 employees of member

firms were admitted and in 1938…the public was admitted. In 1946 it had 1,200 students, the peak thus

far.” Instructors in the Institute were

mostly partners in Stock Exchange firms.

In 1963, in an act reminiscent of Francis Kimball’s original

design, the United States Trust Company broke through three floors to connect

and enlarge their offices at 45 Wall Street.

The Trust Company took a long-term lease on three floors of 37 Wall

Street to seal the plan.

Four years later, the main banking floor would change hands

again. In 1967 it was announced that “Extensive

renovations to provide modern trading floor and administrative offices for the

NYCE are underway in the 25-story tower at 37 Wall Street.” The move lasted until the 1980s when Morgan

Guarantee Trust Company moved in.

Francis Kimball’s handsome building would undergo its most

drastic change when it was renovated and restored by architect Costas

Kondylis. Converted into 373 rental

apartments, its residents enjoy a gym, lounge with pool tables and a screening

room. Above is a landscaped roof garden.

|

| photo by Alice Lum |

The great marble-walled banking room is now a 7,700-square-foot retail space for Tiffany & Co.

The jewelry store returned to lower Manhattan where it started out in

1837. Kimball’s exuberant, lush façade remains

untouched, although its 25 stories no longer tower above its neighbors.

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

A beautiful forgotten ornamented gem of a building

ReplyDelete