Moses Taylor Pyne had the glass and metal marquee installed over the entrance in 1903. from the collection of the New-York Historical Society

Murray Hill was among Manhattan's most prestigious neighborhoods in 1864, its mansions rivaling or surpassing those rising along Fifth Avenue. That year real estate investor John H. Sherwood erected a sumptuous, double-wide residence at the northeast corner of Madison Avenue and 39th Street. Faced in brownstone, its Second Empire style design was the latest in domestic architectural fashion. The rusticated stone basement level supported three floors of brick and a slate-tiled mansard roof crowned with lacy iron cresting. A projecting bay on the side with grouped, arched windows--most likely fronting the dining room--provided a balcony to a second floor bedroom.

The mansion became home to newlyweds Alden Byron Stockwell and his wife, Julia Maria Howe. She was the eldest daughter of Elias Howe, the inventor of the sewing machine. Upon Howe's death in 1867, Julia inherited $2 million--around $36 million today. Tragically, Julia died on March 21, 1869 at the age of 23.

The young stockbroker remained in the Madison Avenue mansion, The Augusta Chronicle saying on March 29, 1873, "His house on Madison avenue, corner of thirty-ninth street, is one of the most elegant and costly in the city. It is furnished in a style of the greatest grandeur. Even the fenders around the grates in the drawing room are of gold."

Described by historian John Haskell Kemble as "a vigorous but incautious young stock operator," Stockwell purchased the Pacific Mail Steamship Co. in 1871. Things could not have looked rosier for the 37-year-old, but his fortunes were about to change.

In 1872, he began construction on an extension at the rear of the Madison Avenue house. But he soon ran afoul of the city. The minutes of the Board of Alderman on August 19, 1872 directed the Commissioner of Public Works "to notify A. B. Stockwell to remove forthwith the projection now being erected on his house, situated on the northeast corner of Thirty-ninth street and Madison avenue...as it is in violation of law by projecting four feet beyond the streetline." The aldermen insisted that should Stockwell not comply, the city would demolish the structure.

But much more serious than an aborted construction project was the Financial Panic of 1873. Stockwell was forced to resign from the Pacific Mail Steamship Co. that year "under a cloud because of his financial administration," according to Kemper. Before long he declared personal bankruptcy, having lost what The New York Times called "a fortune of seven comfortable figures." When his large art collection was auctioned off, the catalogue noted, "Nearly all of his pictures, by American, English and Scotch artists, were painted expressly to his order, and many are the master-pieces of their authors."

The Madison Avenue mansion became home to the family of Jules Reynal Roche Fernoy de St. Michel, "better known in New-York society circles as Jules Reynal," according to The New York Times later. The newspaper called him "a Frenchman of excellent family." He and his wife, the former Nathalie Florence Higgins, had three surviving children, Mathilde Eugenie, Nathaniel Claude, Eugene Suguery. (Jules Regual was born in 1874, but died of scarlet fever in childhood.) The family maintained a summer estate, Rocky Dell Farm, at White Plains, New York.

Nathalie was the daughter of Elias Higgins, a millionaire carpet merchant. Like Julia Stockwell, she was financially independent of her wealthy husband, the Chicago Tribune commenting that she "has a large property."

Social standing and wealth does not preclude domestic abuse. On February 28, 1889 The Evening World reported the "rather startling story concerning the domestic life of Mr. and Mrs. Jules Reynal, who occupy the mansion 263 Madison avenue." The article began saying, "Mr. Reynal is a well-known man about town and is a member of several clubs. His wife is a niece [sic] of E. S. Higgins, the wealthy carpet manufacturer, and is quoted as worth a million dollars."

According to reports, Nathalie had disturbed the quiet of Murray Hill a few nights earlier, around midnight, "by loud cries of 'Help! Police!' which brought neighboring aristocrats bent upon rescue out of their houses and into the streets." Witnesses recounted that Nathalie appeared on the balcony above the entrance "and begged piteously to be saved from her husband, whom she said had not only abused his little son, but had threatened her with a revolver," as reported by The Evening World.

Police entered the mansion "and things quieted down." Jules Reynal left the following morning to spent time in a hunting lodge in North Carolina. While Nathalie refused to speak about the incident, her husband's attorney immediately went into damage control mode. He told a reporter from The Evening World, "Excepting the matter of residence, wealth, family and such incidents, the story is absolutely false...I certainly should not remain on friendly terms with him if anything of this sort had occurred." Nevertheless, the couple separated, with Jules moving into the Park Avenue Hotel.

Mathilde's marriage to Paul Sibert Thebaud in the Church of St. Francis Xavier on January 15, 1890, was a brilliant social affair. The Chicago Tribune noted that Thebaud was the great-grandson of John Schermerhorn and of Nicholas Gilbert, "and the bride also comes of one of the oldest French families in New York." The article said "The wedding gifts were most beautiful and valuable, and the guests at the reception crowded the bride's house, No. 263 Madison avenue. The bride's dowry is said to be $1,000,000."

Jules Reynal died on July 16, 1894 at Rocky Dell Farm. The New York Times noted, "While in his city Mr. Reynal resided at the Park Avenue Hotel, but he also had a residence at 263 Madison Avenue." His estate was left mostly to his three children, who shared "the collection of watches, jewelry, books, paintings, a statue of the Venus de Milo, and other articles of vertu in the house 263 Madison Avenue, to be divided equally among them."

He also left each child $5,000 "with which to purchase a remembrance." He left his step-mouther, Charlotte Victoria Reynal a trust fund of $10,000. There was no mention of Nathalie in the will, either because of tensions between the couple, or simply because she was wealthy in her own right.

Her husband's death seems to have freed Nathalie to move more freely in society. The New York Times later said that following his death, "Mrs. Reynal had gone out a great deal in society, entertaining lavishly at her town house on Madison Avenue and at her country seat at White Plains." She spent the summer social season of 1897 in Bar Harbor, Maine, the New-York Tribune mentioning on August 15, "One of the most elaborate luncheons was given on Wednesday by Mrs. Jules Reynal at Corners Meet, which she has rented for the season."

The Reynals were unafraid of innovations. On May 9, 1900 the New-York Tribune noted, "Among those who have returned to their country seats are Mrs. Jules Reynal and her two sons, Nathaniel and Eugene, who for several days have appeared on the highways in an automobile." Only a week earlier the newspaper had reported on Nathalie's electrifying of the estate, saying "Mrs. Jules Reynal has just had three hundred lights installed at her home, Rocky Dell Farm."

It would be the last summer season for Nathalie at Rocky Dell Farm. In March 1901, the engagement of Eugene to Adelaide Fitzgerald was announced. A large party was held in the country home of Howard Willets, south of White Plains on March 8. Among the many guests, of course, were Mathilde and her husband, Nathalie and Nathaniel.

The following day Eugene and Adelaide were diagnosed with scarlet fever--the disease that had claimed Eugene's baby brother years earlier. The New-York Tribune reported that the couple "each have quarters in the south end of the house, where they are attended by a corps of nurses." None of the guests could leave, but luckily "there are about forty rooms in the Willets house," said the article. It added, "Mr. Reynal's case is the more serious of the two. He was unable to eat yesterday."

Mathilde fell ill with scarlet fever almost immediately. Eugene's condition was so precarious that he and Adelaide were married in his sick room. On March 17, the New-York Tribune reported, "At 10 a.m. Mr. Reynal's condition became so critical that hope for his recovery was almost abandoned. This news was taken to Miss Fitzgerald in her sickroom, with the wish of Mr. Reynal that their marriage be solemnized at once, as he feared that his death was only a few hours off. Miss Fitzgerald consented instantly." No witnesses other than five nurses were allowed into the room.

On March 24, on reporting that their host, Howard Willets had also contracted the disease, the New-York Tribune reported, "The quarantined honeymoon of Mr. and Mrs. Reynal will be continued eight weeks longer, on account of Mr. Willet's sickness."

Nathalie was allowed to return to the Madison Avenue mansion by the end of the month. On March 30 the New-York Tribune reported that she "is ill, though not seriously so, at her house, No. 263 Madison-ave., her indisposition being due to worry and anxiety concerning her son, Eugene, and her new daughter-in-law, nee Fitzgerald, who are now recovering from scarlet fever." In fact, her condition was much worse that most knew. She was battling cancer.

On April 28, 1901, physicians operated on Nathalie in the Madison Avenue house "and removed a cancerous growth of a malignant type," said The New York Times. Two days later the New-York Tribune reported, "So faint are the hopes entertained of the recovery of Mrs. Jules Reynal...that her son Nathaniel was married yesterday by his mother's bedside to Miss Sarah Caldwell Rutter, daughter of Mrs. Nathaniel Rutter, the ceremony being performed by Archbishop Corrigan."

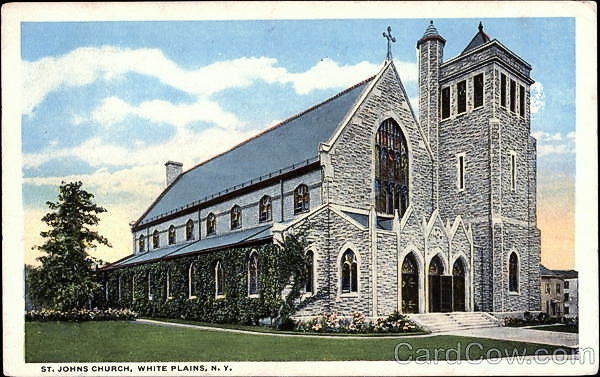

Nathalie survived three more days, dying on May 2, 1901. Her funeral was held at St. John the Evangelist Catholic church in White Plains, which she had erected in memory of her son Jules.

Nathalie Reynal purchased the land and paid for the White Plains church in 1892 as a memorial to her son.

The following year in February the Reynal estate sold the Madison Avenue mansion to Moses Taylor Pyne for $250,000, just over $7.75 million in today's money. Born in 1855, the son of Percy Rivington Pyne and Albertina Shelton Taylor, he was married to Anna Margaretta Stockton, who went by her middle name, in 1880. Educated as a lawyer, Pyne was a graduate of Princeton University, and had inherited a fortune from his maternal grandfather, Moses Taylor. He was a director of four banks, the president of a railroad and sat on the boards of eight others, and was a director in several corporations.

Moses and Margaretta had three sons, Robert Stockton, Percy Rivington and Moses Taylor, Jr. The family's country estate, Drumthwacket, was in Princeton, New Jersey.

Built in 1835, Drumthwacket is today the official residence of the Governor of New Jersey. photo by KForce

The Pynes immediately set out to update the vintage Madison Avenue residence. In 1903, they had modern plumbing installed and also hired The Snead & Co. Iron Works to fabricate "ornamental railing, entrance gates and marquise." (The French style glass and iron marquee was a noticeable add-on.)

Robert Stockton Pyne's engagement to Constance S. Pratt was announced on January 3, 1903. Tragically, the wedding would never come to pass. The 20-year-old groom-to-be died the following month, on February 27.

For years to come, the Pynes were highly visible in society, both in Manhattan and New Jersey. Moses remained highly involved with Princeton University. He was not only a trustee of the school, but was among its largest benefactors. As chairman of the Committee on Grounds and Buildings, he was highly responsible for the appearance of the campus, staunchly advocating the Collegiate Gothic architectural style.

On January 24, 1921, the New York Herald reported, "Mr. Moses Taylor Pyne, who has been seriously ill at his home, 263 Madison avenue, has had a slight change for the better." He would never truly recover, however, and he died in the house on April 22 of bronchial pneumonia.

According to The New York Times on May 5, "the total fortune left by Mr. Pyne was about $100,000,000." That figure would translate to $1.45 billion today. His surviving sons, Percy and Moses, shared in the bulk of the estate, with Margaretta receiving Drumthwacket and the Madison Avenue mansion. Princeton University received real estate and other gifts amounting to about $100,000.

Margaretta spent more and more time at the New Jersey estate. Nevertheless, according to The New York Times, when real estate operators began buying up blocks of Murray Hill property for commercial development, she told a friend "I will never give up this house."

Margaretta's health began to fail in 1936. She died in her Madison Avenue home on April 22, 1939 at the age of 83. Percy, now the only surviving child, inherited the mansion.

On December 7, 1943, two years after America was pulled into World War II, The New York Sun announced, "The Pyne House, 263 Madison avenue, will be opened to men and women of the armed forces on Saturday by the war commission...which has leased the building for the duration as a fraternal center and canteen." The residence now provided sleeping accommodations for 100 to 125 military personnel. Overnight lodging and breakfast cost 50 cents.

The Pyne House, while still being operating as a military canteen, was sold in April 1946. The new owner, said The New York Times, "plans to improve the corner with a new twelve-story business building for the textile trade." The ambitious plans were scaled back, and a Modernist five story structure was completed on the site in 1949.

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

.png)

Thanks so much! Just what I was looking for, I was interested in Percy Rivington Pyne 2nd and saw the family's connection to this address. What a surprise to find such detailed information and photos.

ReplyDeleteI'm gratified to hear that my articles are helpful to research like yours. Thanks for writing.

Delete