In 1891 prolific developer James T. Hall began construction of four brownstone-fronted homes on the north side of West 75th Street, between Central Park West and Columbus Avenue. Designed by George H. Budlong, they were a creative blend of Renaissance Revival and Romanesque Revival architecture.

|

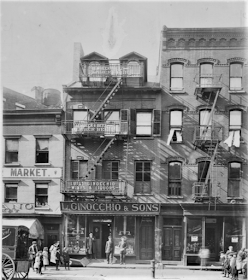

| No. 51 stands out among the row because of its intact condition and later-added mansard. |

The homes were completed in 1891. Four stories tall above English basements, their 23-foot width and proximity to the park reflected the comfortable financial status of their intended owners. No. 51, overall, featured the elements of the Renaissance Revival style, but it owed its rough-cut brownstone face to Romanesque Revival. A robust box stoop led the the double-doored entrance, framed in Renaissance-inspired pilasters. The handsome three-sided oriel at the second floor, supported by a swagged bracket, provided a balcony to the third floor. Above it all, originally, a modest modillioned pressed metal cornice matched those of its neighbors.

|

| A delicate carved ribbon goes nearly unnoticed within the rough brownstone blocks. |

When the original owner of the house lost it in foreclosure in 1894, it was purchased by Walther (sometimes anglicized as Walter) Luttgen for $34,500--just over $1 million today. Born in Germany in 1839, he was a partner with August Belmont in the banking firm August Belmont & Company. Luttgen and his wife, the former Amelia Victoria Bremeyer, had two daughters, Florence Amelia, born in 1868, and Gertrude Marion, born in 1880.

Walter was active in the yachting community and was a member of the Seawanhaka Corinthian Yacht Club and the Columbia Yacht Club. When his yacht, the Linta, was launched in July 1892, The Evening World mentioned "The Linta is 85 feet long, handsomely fitted up and one of the largest steam yachts ever built here."

Fashionable New Yorkers filed into the 75th Street house on January 39, 1901 for Gertrude's wedding reception following she her marriage to Oliver Hildreth Keep, Jr. in All Angels' Church. (Sadly, Gertrude died seven years later at the age of 28.)

Luttgen's business interests went beyond banking. In January 1900 he and August Belmont had purchased an entire block of Harlem real estate; and he was a director of the Illinois Central Railroad Company, the Rapid Transit Construction Company, the Consolidated Railway Electric Lighting and Equipment Company, and the Transatlantic Trust Company.

In March 1902 the Luttgens sold No. 51 to Rev. John Henry Watson and his wife, the former Susan Matilda Hoffman. The couple had two sons, Henry and Eugene, and a daughter, Mary Elmendorf, all of whom were grown by now. Mary and Eugene, both unmarried, moved into the house with their parents.

Born in 1845 to the Boston minister Rev. John Lee Watson, Watson had an impressive background and traced his ancestors to the Mayflower. Upon graduating from the Berkeley Divinity School in Middleton, Connecticut, he had immediately become assistant rector at the fashionable Trinity Chapel in Manhattan. He then moved on to churches in Stamford, Philadelphia, Hartford and New Rochelle. Returning to New York City, he gave up parish work and devoted himself to the missions in the impoverished areas.

|

| Walther Luttgen - Columbia Yacht Club, 1917 |

Walter was active in the yachting community and was a member of the Seawanhaka Corinthian Yacht Club and the Columbia Yacht Club. When his yacht, the Linta, was launched in July 1892, The Evening World mentioned "The Linta is 85 feet long, handsomely fitted up and one of the largest steam yachts ever built here."

Fashionable New Yorkers filed into the 75th Street house on January 39, 1901 for Gertrude's wedding reception following she her marriage to Oliver Hildreth Keep, Jr. in All Angels' Church. (Sadly, Gertrude died seven years later at the age of 28.)

Luttgen's business interests went beyond banking. In January 1900 he and August Belmont had purchased an entire block of Harlem real estate; and he was a director of the Illinois Central Railroad Company, the Rapid Transit Construction Company, the Consolidated Railway Electric Lighting and Equipment Company, and the Transatlantic Trust Company.

In March 1902 the Luttgens sold No. 51 to Rev. John Henry Watson and his wife, the former Susan Matilda Hoffman. The couple had two sons, Henry and Eugene, and a daughter, Mary Elmendorf, all of whom were grown by now. Mary and Eugene, both unmarried, moved into the house with their parents.

Born in 1845 to the Boston minister Rev. John Lee Watson, Watson had an impressive background and traced his ancestors to the Mayflower. Upon graduating from the Berkeley Divinity School in Middleton, Connecticut, he had immediately become assistant rector at the fashionable Trinity Chapel in Manhattan. He then moved on to churches in Stamford, Philadelphia, Hartford and New Rochelle. Returning to New York City, he gave up parish work and devoted himself to the missions in the impoverished areas.

Watson had also provided his services as the chaplain of the

Army and Navy Aid Association. The group

provided help to veterans, many of whom had served in the recent

Spanish-American War. In the minutes of

a meeting opened by Watson on May 18, 1900, it was noted “Many pathetic letters

have been received, the most of them containing requests for work.”

Susan also came from a religious family. Her father was Rev. Eugene Augustus Hoffman, Dean of the General Theological Seminary. Newspapers called him "the richest clergyman in the world." Upon his death on June 17, 1902, three months after the Watsons purchased No. 51, he died leaving an estate of just under $10 million. It was divided mainly between his widow and four children.

In March 1904 the Watsons made extension renovations to the 75th Street house. They hired the well-known architectural firm of John B. Snook & Son to do the equivalent of $87,000 today in work that included adding a mansard level, rearranging the interior walls and closets, and install new windows. A hefty cornice visually capable of upholding the new level was installed at the time.

The Watson summer estate was Ondawa on Little Moose Lake in Old Forge, New York. Susan involved herself in social circles there and was a member of the Adirondack League Club.

Essentially retired, Watson filled his time with writing. In 1911 he published The History of Fra Paolo Sarpi, a biography of the 18th century priest who was openly critical of the Catholic Church.

Watson suffered a fatal heart attack in the 75th Street house on October 31, 1913 at the age of 68. His funeral was held in Trinity Chapel. Susan continued to live in the house with Mary and Eugene and to summer at Ondawa. She busied herself with charities such as the Fifth Avenue Hospital and the Hospital Musical Association.

Susan's mother, Mary C. Hoffman, died in 1914. Given her massive estate and the individual wealth of her children, it is perhaps a bit surprising that a court battle broke out over jewelry. Susan's siblings protested when the executors omitted two items from the estate inventory--a pearl necklace and a ruby ring valued at $12,500 (just under $325,000 today). The Sun reported on July 19 "Mrs. Watson insisted that her mother, who had other jewelry worth $38,605, gave to her the necklace and ruby ring long before death."

The suit against Susan was not the only contention. Mary's grandchildren separately sued because she had bequeathed her "large retinue of servants" four months salary. Commenting on that suit, the judge said "It certainly is not the custom among affluent families to turn servants of dead people summarily out of doors."

Susan and Mary traveled together. On October 23, 1921, for instance, The New York Herald reported that they were pausing at the Maplewood Hotel in Pittsfield, near Lenox, Massachusetts.

Perhaps assuming that Mary would stay forever single, society may have been surprised when Susan announced her engagement to the Rev. Jackson H. Randolph Ray of Dallas, Texas on April 17, 1922. The wedding took place on July 18 in fashionable St. Thomas's Church on Fifth Avenue. Ray was Dean of St. Matthew's Cathedral in Dallas. Two days prior to the ceremony The New York Herald predicted "Late in the season as it is, there will be many notable members of old New York society present."

Two years later, on August 28, 1926, The Sun reported that Susan had sold No. 51 to the Hephzibah House Bible Training School and Home of Rest. The institution paid $32,000 for the property, or about $469,000 in today's money.

The organization was founded in 1893 as the Hephzibah House and Training School for Christian Workers, a Bible training school for young women. Its name was changed in 1897 when it began operating a lodging house for missionary workers passing through New York, as well.

A 1939 renovation resulted in a kitchen and laundry in the basement, a reception room and library on the first floor, and furnished rooms on the floors above.

The Hephzabah House Bible Training School and Home of Rest remains in the Luttgen house, its website noting "It continues to serve as a guest house for those serving in ministry to be able to visit New York City for meetings, vacation or rest to stay in Manhattan at affordable rates."

photographs by the author

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com